Rent Deceleration Signals Fed Relief: What Renters Should Do Now

The ongoing deceleration in U.S. rental price growth is emerging as a primary disinflationary force, significantly impacting the core Consumer Price Index (CPI) and bolstering expectations for a less restrictive Federal Reserve monetary policy.

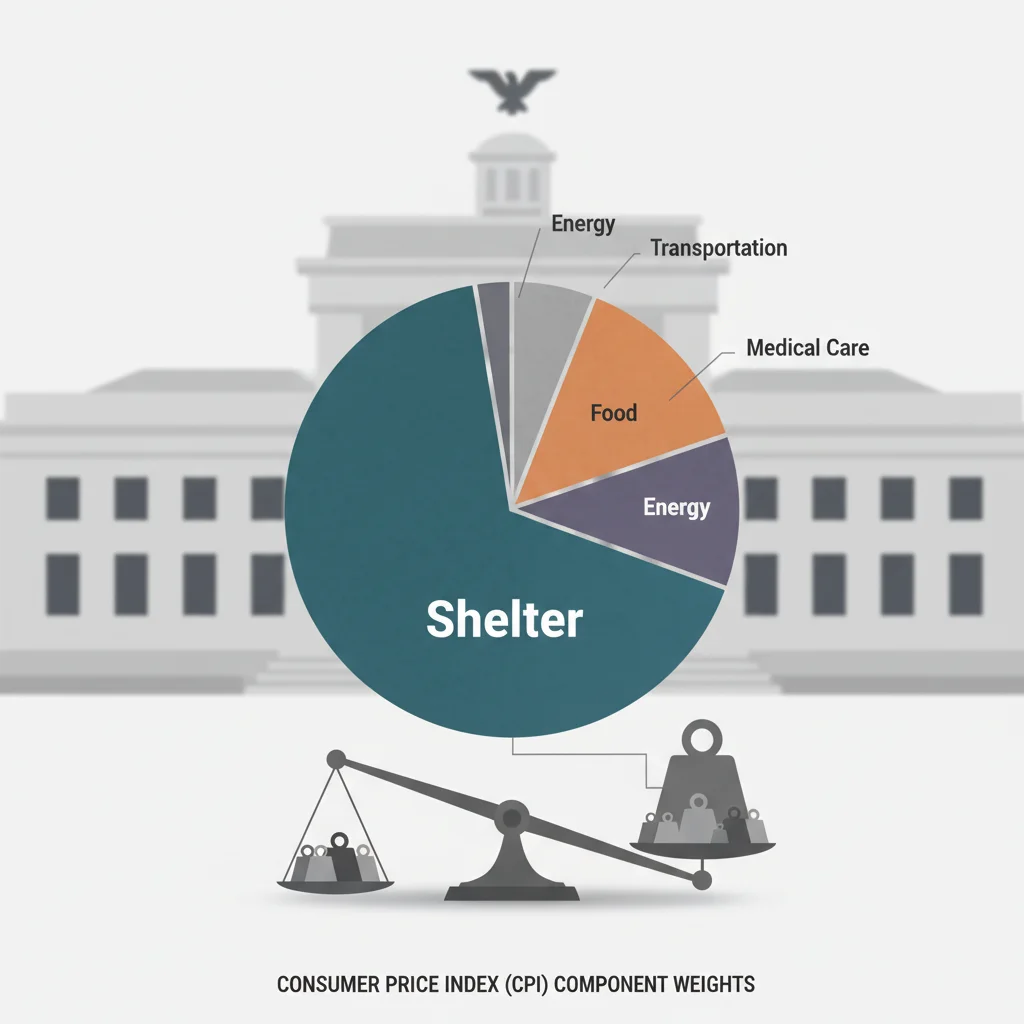

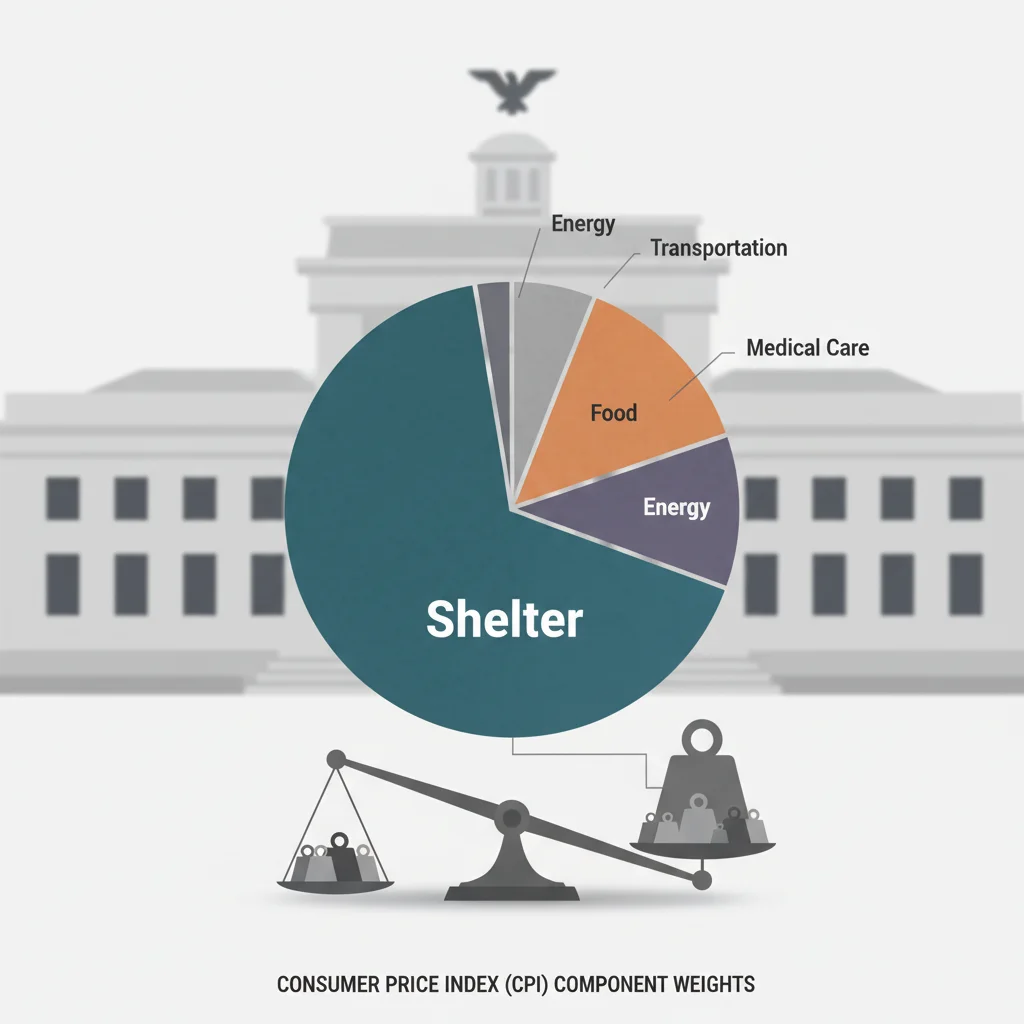

The most recent housing data confirms a pivotal shift in the inflation narrative: the pace of rental price increases is slowing markedly, offering critical context for the Federal Reserve’s ongoing battle against entrenched inflation. This trend, known as rent deceleration signals, acts as a leading indicator for the core Consumer Price Index (CPI), given that the shelter component—which heavily relies on rental data—constitutes approximately one-third of the index. For millions of Americans, this economic pivot is not merely an abstract data point; it fundamentally alters the calculus of household budgeting and suggests a potential easing of the central bank’s aggressive rate-hiking cycle, impacting everything from mortgage rates to job market stability. The question for renters now is how to strategically leverage this shift in market dynamics.

The mechanics of shelter inflation and the Fed’s dilemma

Understanding the Federal Reserve’s reaction function requires dissecting how shelter costs are measured and their immense weight within the primary inflation metrics. The shelter component, comprising Owners’ Equivalent Rent (OER) and primary rents, accounts for roughly 33% of the CPI basket and approximately 40% of the core CPI (excluding food and energy). This immense weighting means that even if commodity prices stabilize, persistently high shelter costs can keep the overall inflation rate elevated, complicating the Fed’s path toward its 2% target. Historically, changes in market rents, as measured by private indices like Zillow or Apartment List, lead the official government data by a lag of 9 to 18 months, primarily due to the way the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) surveys existing leases.

As of the latest data release—reflecting leases signed months ago—official CPI shelter inflation remains stubbornly high, even as real-time market rents have plateaued or fallen in many major metropolitan areas. For instance, while the CPI measure of rent rose 0.5% month-over-month in the most recent reading, private sector data showed median asking rents for new leases fell year-over-year in cities like Phoenix, Arizona, and Austin, Texas, by over 3% and 5% respectively, according to recent analysis from Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. This divergence creates the Fed’s dilemma: policymakers must maintain a restrictive stance based on lagging official data while acknowledging that forward-looking indicators point toward significant disinflationary pressure. The market is now keenly focused on the convergence of these two data sets.

The supply response and vacancy rates

A key driver of the rent deceleration signals is the robust supply response in the multi-family sector. Following the pandemic-era housing boom, developers rushed to build new units, leading to a record number of apartments currently under construction. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicates that multi-family completions have surged, with many projects initiated in 2021 and 2022 now hitting the market. This influx of supply directly increases vacancy rates, which, in turn, reduces landlords’ pricing power.

- Multi-family Completions: The number of completed units reached multi-decade highs in the second half of the year, particularly in Sunbelt markets, where construction was fastest.

- Vacancy Rates: The national apartment vacancy rate has edged up toward 6.5% as of Q3, a significant increase from the historical lows of 4.8% seen in early 2022. This higher rate signals improved bargaining leverage for prospective renters.

- Asking vs. Effective Rent: Landlords are increasingly offering concessions (e.g., one month free rent) to fill units, meaning the effective rent paid by tenants is falling faster than the stated asking price. This dynamic will gradually filter into the official CPI data.

The implications for the Federal Reserve are clear: if the pipeline of new housing supply continues to flood the market, the dominant source of inflation—shelter—will inevitably cool, allowing the Fed to potentially pause or even reverse its rate hikes sooner than anticipated. Economic models suggest that a sustained drop in the official CPI shelter component to a 3% annualized rate is necessary to bring core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge) back toward the target, a scenario becoming increasingly plausible due to the current rent deceleration signals.

Macroeconomic implications for Fed policy and interest rates

The trajectory of rental inflation is arguably the single most important factor determining the Federal Reserve’s next moves. Jerome Powell and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) have repeatedly emphasized that while goods inflation has normalized, service sector inflation, particularly housing, remains sticky. The latest data showing market rent stagnation provides a credible path for the Fed to achieve its goals without triggering a severe economic downturn.

Analysts at institutions like JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America have updated their Fed forecasts, citing falling shelter inflation as a primary reason for anticipating rate cuts starting in the latter half of the year. The consensus view suggests that as the lagging CPI shelter component finally reflects the real-time market softening, core inflation could drop sharply, potentially reaching 2.5% annualized by the end of the fiscal year. This anticipation has already been priced into the bond market, leading to a noticeable compression in the yield curve and lower expected future short-term rates. Lower interest rates, in turn, reduce the cost of capital for businesses and eventually ease the burden on consumers, creating a virtuous cycle of economic stability.

The impact on mortgage rates and housing affordability

While the rent deceleration signals directly affect renters, the broader housing market is also influenced by this trend. Lower expected inflation due to decelerating rents reduces the pressure on the Fed to maintain high policy rates. When the Fed signals a potential shift toward easing, long-term Treasury yields—which mortgage rates track closely—tend to fall. This dynamic is crucial for aspiring homeowners.

- Long-Term Yields: A sustained belief that inflation is receding, driven by housing, pushes down the 10-year Treasury yield, which is the benchmark for 30-year fixed mortgage rates.

- Affordability Boost: Lower mortgage rates improve housing affordability, potentially drawing some renters out of the rental market and into homeownership, further easing demand pressure on rentals.

- Investor Sentiment: Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) focused on residential property may see slower revenue growth due to reduced rental increases, but the prospect of lower borrowing costs can improve their long-term valuation outlook.

The interconnectedness of the housing and bond markets means that renters benefit not only from slower rent increases but also from the potential for cheaper borrowing costs should they decide to purchase a home. This broader macroeconomic context underscores why the rent data is being watched with such intensity by Wall Street and Main Street alike.

Actionable strategies for current renters

For current renters whose leases are nearing expiration, the cooling market presents a unique opportunity to negotiate more favorable terms. The prevailing environment of increased supply and rising vacancy rates shifts the bargaining power away from landlords, a reversal from the highly competitive environment of 2021 and 2022. Renters should approach their lease renewal with hard data and a clear understanding of local market conditions.

Leveraging market data in negotiations

The critical first step is research. Relying solely on the national average is insufficient; success depends on knowing the specific trends in your submarket. Use real-time data sources (like Zillow Observed Rent Index or Apartment List National Rent Report) to establish the current median asking price for comparable units within a half-mile radius of your location. If new asking rents for similar units are flat or declining, this provides strong leverage against proposed rent hikes.

When negotiating, do not simply ask for a lower price; present the data. For example, if your landlord proposes a 7% increase, but market data shows comparable units are renting for 2% less than the prior year, you have a strong, data-backed case. Focus on the concept of ‘effective rent’—the total cost after concessions. If a neighboring property is offering one month free on a 12-month lease, that effectively reduces the monthly rent by 8.33%. Demand similar concessions or a lower base rate. This strategy is particularly effective in markets experiencing significant supply saturation, such as parts of Florida, Texas, and the Carolinas.

The shift in the market means that landlords are prioritizing occupancy stability over aggressive price increases. Losing a tenant requires turnover costs, including cleaning, marketing, and potential vacancy periods, which can easily outweigh a modest reduction in the renewal rate. Renters with a good payment history are, therefore, highly valuable assets, and this should be explicitly stated during negotiations. Aim for an increase that is at or below the core PCE inflation rate, currently hovering around 3.5% to 4.0%, presenting this as a fair, inflation-adjusted renewal rate.

Analyzing regional disparities in rent deceleration

The rent deceleration signals are not uniform across the United States. The housing market remains highly localized, and while nationally the trend is cooling, significant regional disparities persist. The cooling is most pronounced in the high-growth Sunbelt metros that saw the steepest price increases during the pandemic, while certain high-cost coastal markets, constrained by regulatory hurdles and limited developable land, are experiencing slower, but still positive, growth.

Metropolitan market segmentation

The largest deceleration is consistently seen in markets where construction was easiest and fastest. For instance, according to data from CBRE, markets like Dallas, Texas, and Atlanta, Georgia, have absorbed thousands of new units, leading to year-over-year declines in average asking rents for new leases. The primary factor here is the elastic supply curve—developers can quickly respond to demand.

- Sunbelt Markets (High Deceleration): Characterized by high vacancy rates (often above 7%) and aggressive concessions. Renters here have maximum leverage.

- Northeast/Midwest Core Cities (Moderate Deceleration): Supply is tighter, but demand has stabilized. Rent growth is positive but slowing, offering moderate negotiation room. Cities like Boston and Chicago fall into this category.

- West Coast Coastal Hubs (Sticky Rents): Markets such as San Francisco and New York City, which have high regulatory costs and strong job markets, continue to see rent growth, albeit slower than previous peak years. Negotiation leverage is weaker, but still present compared to the 2022 frenzy.

This regional analysis is vital for predicting the timeline of the Fed’s response. If deceleration remains concentrated in the Sunbelt, the overall national CPI impact will be milder and slower than if the deceleration spreads rapidly to major coastal economic hubs. Financial analysts are closely monitoring these geographic shifts, as they dictate the speed at which shelter inflation will normalize toward pre-pandemic levels of 2% to 3% annualized growth.

The risk of reacceleration and future demand shocks

While the current data points toward sustained rent deceleration signals, economic forecasting requires acknowledging risks, particularly the potential for a reacceleration of demand. The primary risk factor stems from the job market. If the U.S. labor market remains exceptionally robust, with low unemployment (currently near 3.9% as of the latest BLS report) and strong wage growth (annualized growth above 4.1%), household formation could rebound sharply. Increased household formation, where more young adults or roommates decide to live independently, directly translates into higher demand for rental units.

Monitoring wage growth and household formation

Wage growth, particularly in the service sector, remains a challenge for the Fed. While real wages (adjusted for inflation) are finally turning positive for many workers, this continued income strength fuels the capacity to pay higher rents. If construction activity slows down due to high financing costs, and demand remains strong due to robust employment, the current disinflationary trend in rent could stall or reverse.

Furthermore, the single-family housing market remains largely unaffordable for first-time buyers due to elevated mortgage rates (average 30-year fixed rate hovering near 7.0%). This forces potential buyers to remain in the rental pool longer, maintaining structural demand for apartments. Analysts at Moody’s Analytics project that housing affordability will remain constrained until either mortgage rates drop below 5.5% or housing prices undergo a more significant correction, keeping a floor under rental demand.

Therefore, while the current deceleration is a positive sign for inflation, the long-term outlook depends on a delicate balance between new supply absorption and persistent structural demand fueled by a strong labor market and constrained homeownership. The Fed must navigate this complexity, recognizing that excessive easing could reignite demand and undermine the progress achieved in the rental market.

The long-term outlook for housing and the CPI

The consensus among leading economic consultancies, including those at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, is that the lagging effect of market rent deceleration will become fully visible in the official CPI data over the next 12 to 18 months. This suggests that the disinflationary pressure from housing is locked in, providing a crucial tailwind for the Fed’s efforts, regardless of short-term volatility in energy or goods prices. The key is the magnitude—how far and how fast the official shelter component falls.

Forecasting the trough in rent inflation

Most financial models predict that the year-over-year rate of CPI shelter inflation, currently elevated, will peak and then decline steadily, potentially hitting 3.0% by the end of next year. This forecast is based on the assumption that the high volume of multi-family units currently under construction will be successfully absorbed by the market without a sudden surge in demand.

The implications for financial markets are profound. If the housing component successfully disinflates, it removes the largest impediment to achieving the Fed’s 2% inflation target. This would likely solidify the timetable for rate normalization, potentially leading to lower borrowing costs across the economy. Investors are already rotating capital toward sectors that benefit from lower long-term interest rates, such as growth stocks and residential REITs that have stable balance sheets.

For renters, the long-term outlook suggests a return to a more normalized environment where rental increases track general inflation and wage growth, rather than outpacing them dramatically. This restoration of balance, driven by increased supply and the Fed’s restrictive policy, is a fundamental step toward improved economic stability and household savings rates. The current rent deceleration signals are a powerful reminder of how supply chain dynamics, construction cycles, and monetary policy ultimately intersect to determine the cost of living for millions of Americans.

| Key Factor/Metric | Market Implication/Analysis |

|---|---|

| CPI Shelter Component Weight | Represents ~33% of CPI. Deceleration is essential for reaching the Fed’s 2% inflation target. |

| Market Rent vs. CPI Rent Lag | Real-time market rent changes lead official CPI data by 9–18 months. Current deceleration suggests future CPI relief. |

| Multi-Family Vacancy Rate | Rising vacancy rates (approaching 6.5%) indicate increased supply and reduced pricing power for landlords. |

| Renter Negotiation Strategy | Renters should use local market data on concessions and new asking rents to negotiate renewal rates below 4%. |

Frequently asked questions about rent deceleration and Fed policy

The impact is indirect but significant. While the official CPI shelter component lags, strong real-time rent deceleration provides the Fed with forward guidance that inflation is cooling. This bolsters confidence for a potential pause or pivot in monetary policy within the next 6 to 12 months, contingent on sustained labor market stability.

Renters should utilize localized, real-time data from private indices (e.g., Zillow, Apartment List) showing median asking rents and concession rates for comparable units. Presenting evidence of year-over-year declines in effective rent in your specific submarket provides strong leverage against proposed increases exceeding 3% to 4%.

No, the deceleration is highly localized. It is most pronounced in Sunbelt metros like Phoenix and Austin, where multi-family supply surged. Coastal, supply-constrained markets like New York and Boston show slower rent growth but generally avoid outright declines, requiring renters in those areas to negotiate more cautiously.

Slower rental growth translates to reduced revenue growth for residential REITs, potentially pressuring short-term earnings. However, the expectation of future Fed rate cuts, driven by falling inflation, could lower their borrowing costs and improve long-term asset valuations, balancing the negative revenue impact.

The primary risks include a sustained, robust rebound in household formation fueled by strong wage growth (currently above 4%) coupled with a sharp reduction in new multi-family construction due to high capital costs. If supply slows while demand remains strong due to constrained homeownership, rents could quickly reverse their downward trend.

The bottom line

The emergence of clear and sustained rent deceleration signals represents a crucial inflection point in the U.S. economic cycle, signaling that the most stubborn component of inflation is finally yielding to market forces and monetary policy restraint. For the Federal Reserve, this trend provides the necessary evidence—albeit delayed in official data—to justify a shift away from aggressive tightening, easing the pressure on long-term interest rates. For U.S. renters, the environment has fundamentally changed, moving from a landlord’s market to a more balanced negotiation landscape. Renters nearing lease expiration must leverage local vacancy rates and concession data to secure favorable terms, aiming for renewal rates that reflect the current disinflationary reality, ideally below 4% annualized growth. While risks remain—particularly from a resilient labor market—the structural addition of housing supply offers a powerful and persistent disinflationary force, setting the stage for improved housing affordability and macroeconomic stability over the next two years. Financial markets will continue to scrutinize every official CPI release for confirmation that the lag is closing, cementing the path for the Fed’s eventual policy normalization.