Senior Housing Shortage: The $300 Billion Investment Gap

The confluence of rapidly aging US demographics and insufficient capital allocation has created a critical senior housing investment gap estimated at $300 billion, demanding immediate and strategic private and public sector intervention to avoid a looming social and economic crisis.

The United States is confronting a structural deficiency in specialized residential care, manifesting as a profound senior housing investment gap. This deficit, conservatively estimated by industry analysts and economic forecasts to exceed $300 billion over the next decade, represents the capital required to meet the housing and care needs of the accelerating Baby Boomer demographic. Understanding this gap is crucial, not just for healthcare providers, but for institutional investors, real estate developers, and policymakers, as the failure to address it carries significant macroeconomic and social implications.

The demographic imperative driving demand

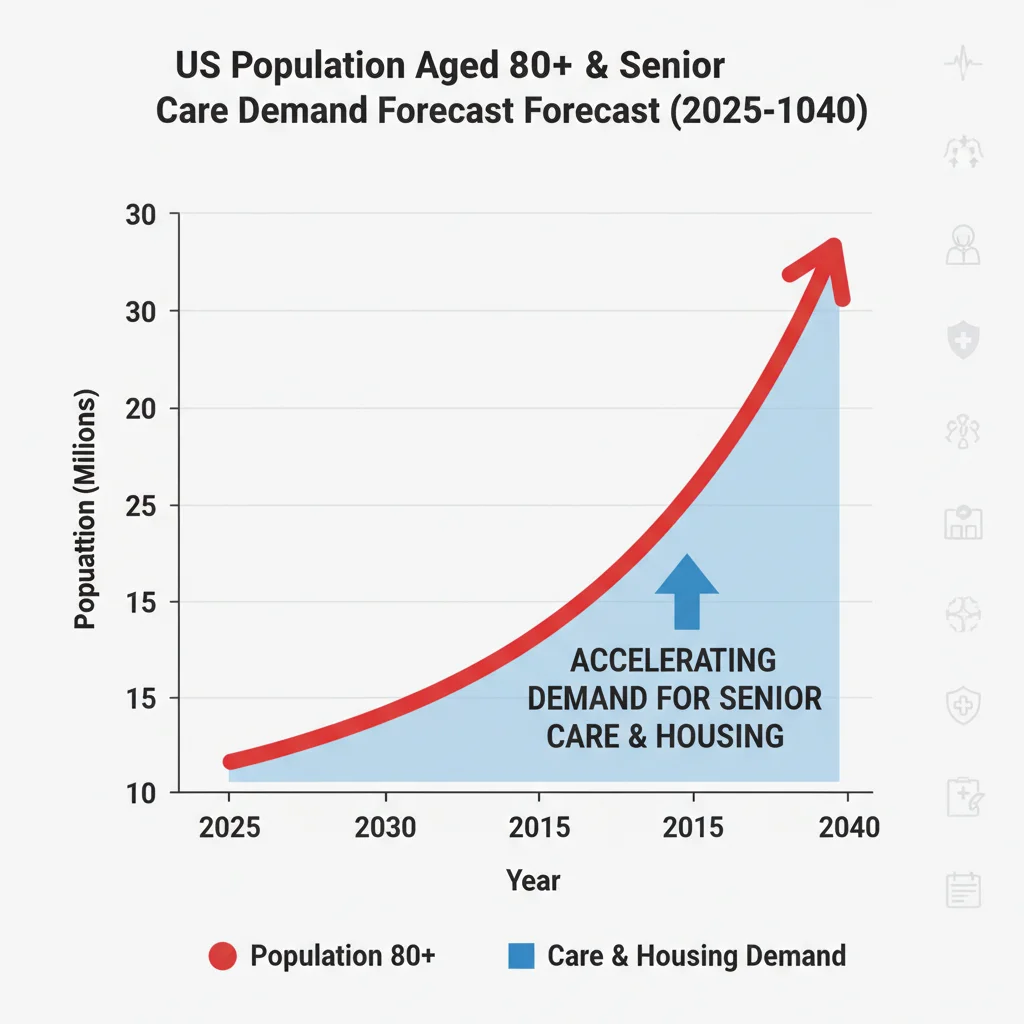

The primary driver of the senior housing crisis is straightforward demography. The Baby Boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964) began turning 65 in 2011, and the cohort requiring higher levels of specialized care—those aged 80 and above—is set for unprecedented growth. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the population aged 85 and older is projected to nearly double from approximately 6.7 million in 2020 to over 14 million by 2040. This rapid expansion creates a massive, inelastic demand shock for housing options that offer services ranging from independent living to skilled nursing facilities.

Current supply metrics fail to keep pace with this trajectory. The construction pipeline for new senior living units has been constrained by escalating development costs, tighter financing conditions following interest rate hikes, and severe labor shortages within the healthcare sector. Analysts at leading commercial real estate firms, including CBRE and JLL, suggest that the current annual completion rate of new units lags behind the required rate by at least 25% to maintain current occupancy levels, let alone absorb the coming demographic wave. This supply-demand imbalance is the fundamental economic friction point.

The 80+ age cohort acceleration

Focusing on the 80+ cohort is essential because this group typically requires the most capital-intensive housing types, such as assisted living and memory care. These facilities have higher operational costs, greater regulatory burdens, and require specialized infrastructure, translating directly into higher development capital needs per unit compared to standard multi-family housing.

- Required Unit Growth: Estimates suggest that approximately 800,000 new senior living units will be needed by 2035 just to maintain the current ratio of available units to the target population, according to NIC (National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care) research.

- Investment Per Unit: The average cost for developing a new assisted living unit often exceeds $350,000, depending on location and amenities, pushing the total capital requirement into the hundreds of billions.

- Regional Disparities: Demand is particularly acute in high-cost-of-living metropolitan areas and Sun Belt states experiencing high levels of senior migration, exacerbating local investment shortfalls.

The gap is defined by the difference between the projected capital expenditure required to construct and staff these necessary units and the currently committed public and private investment. Economists emphasize that this is not merely a quantitative shortage of beds, but a qualitative deficit in the type of housing needed—affordable, integrated, and medically supportive. Failing to close this gap will likely result in increased strain on acute care hospitals and a surge in unmet social care needs, imposing far greater costs on the public sector than proactive investment would require.

Capital market constraints and financing hurdles

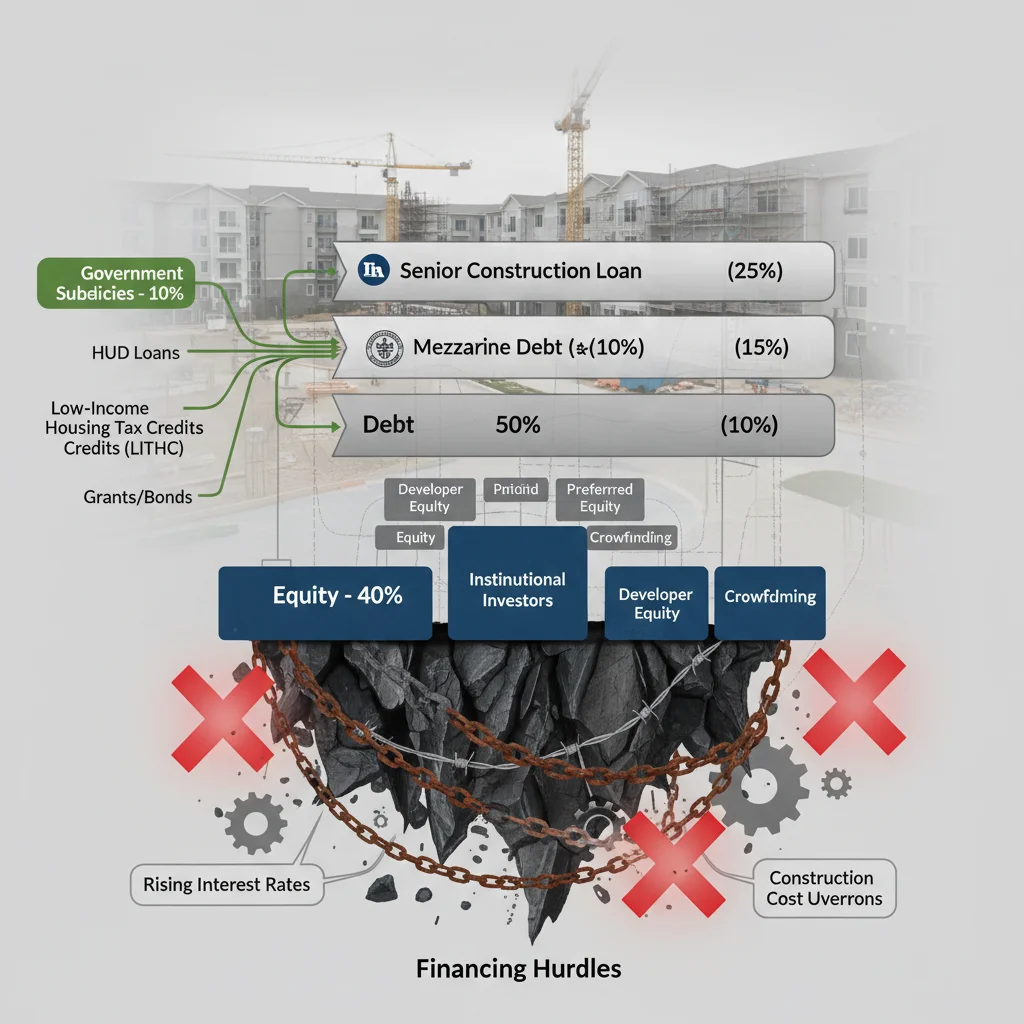

While the demand signal is strong, the flow of capital into the senior housing sector remains insufficient to bridge the $300 billion gulf. Historically, senior housing has been viewed by some institutional investors as a hybrid asset class—part real estate, part operating business—which introduces complexity and perceived risk that deters traditional commercial real estate (CRE) funds.

The current macroeconomic environment has amplified these financing hurdles. The rapid increase in the Federal Reserve’s benchmark interest rate since 2022 has dramatically raised the cost of debt financing for new construction. Developers relying on floating-rate construction loans face significantly higher debt service obligations, pushing required internal rates of return (IRRs) higher and making marginal projects financially unviable. Furthermore, regional banks, which are often key providers of senior housing construction financing, have tightened lending standards in response to broader CRE market distress, limiting access to crucial capital.

The challenge of underwriting operational risk

Unlike conventional apartments, senior housing performance is heavily dependent on operational excellence and healthcare staffing, making underwriting more complex. The operating expense ratio (OER) in senior housing is substantially higher than in multi-family real estate, often exceeding 65% due to labor costs, food service, and utilities. The persistent shortage of nurses and certified nursing assistants (CNAs) has forced operators to offer higher wages and signing bonuses, squeezing net operating income (NOI).

Investment funds, particularly those with a purely real estate focus, struggle with volatility inherent in the operational side. This difficulty is reflected in capitalization rates. While Class A multi-family cap rates might hover around 4.5% to 5.5% in major markets, senior housing cap rates often require a premium, typically ranging from 5.5% to over 7.0%, to compensate for the operational risk. This higher required return further restricts the feasibility of new development in a high-interest-rate environment.

- Labor Cost Pressure: The median hourly wage for CNAs increased by over 15% between 2020 and 2023, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, directly impacting operator margins and investor confidence.

- Lender Caution: Many traditional lenders now require higher loan-to-value (LTV) ratios and stronger pre-leasing commitments for senior housing projects compared to pre-pandemic standards.

- Recapitalization Needs: A significant portion of existing senior housing stock is aging, requiring substantial capital expenditure for modernization and compliance, diverting available funds from new construction.

The consequence is a market failure: immense, verified demand exists, yet high capital costs and perceived operational risk prevent the necessary allocation of private investment to meet the $300 billion need. Bridging this gap requires innovative financing structures that effectively de-risk the operational component for real estate investors while ensuring high-quality care delivery.

The role of specialized real estate investment trusts (REITs)

Specialized healthcare Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) are the largest institutional holders of senior housing assets and play a critical role in addressing the investment shortfall. Companies like Welltower (NYSE: WELL) and Ventas (NYSE: VTR) have deep expertise in the sector, operating under various ownership structures, including triple-net leases and RIDEA (REIT Investment Diversification and Empowerment Act) structures.

These REITs act as long-term capital providers, offering stability to the market. However, even these large players are sensitive to market conditions. During periods of high volatility or operational instability (such as the pandemic-induced labor crisis), REIT stock performance can suffer, limiting their ability to raise equity capital for large-scale development projects. Their investment strategy often prioritizes acquiring existing, stabilized assets or partnering with proven operators, rather than undertaking ground-up development, which carries higher risk and longer gestation periods.

Creative financing mechanisms for development

To unlock the $300 billion needed for new development, analysts are promoting the use of public-private partnerships (PPPs) and subsidized financing tools. One promising avenue is the integration of housing and healthcare finance. For example, some states are exploring blending Medicaid and Medicare funding streams with housing capital to support the construction of integrated care models, particularly for low- and middle-income seniors who represent a growing segment of the need.

- Tax Credits: Expanding the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program to specifically incentivize senior housing development, particularly for middle-market segments, could significantly lower the cost of capital.

- Government-Backed Lending: Utilizing FHA-insured loans (specifically Section 232) can offer more favorable, long-term financing than conventional bank loans, reducing interest rate risk for developers.

- Social Impact Bonds: Issuing bonds tied to measurable social outcomes, such as reduced hospital readmission rates achieved through integrated senior care facilities, can attract ESG-focused institutional capital.

The consensus among financial strategists is that the private sector cannot solve this issue alone. Government intervention, particularly in lowering the effective cost of capital and mitigating operational labor risk through policy, is necessary to make a significant dent in the projected investment gap. A failure to introduce these mechanisms will likely mean that only high-end, luxury senior living is developed, leaving the vast majority of middle-income seniors underserved.

The underserved middle market and affordability crisis

The most pronounced component of the senior housing investment gap is concentrated in the middle market. This segment comprises seniors whose annual incomes are too high to qualify for subsidized housing (like Medicaid-funded nursing homes) but too low to afford the average private-pay assisted living costs, which often exceed $5,000 per month nationally.

According to research by the National Council on Aging, approximately 54% of future seniors are projected to fall into this middle-income bracket, defined as having assets and income that will allow them to pay between $40,000 and $75,000 annually for housing and care. The current market offers very few viable options for this group. New construction overwhelmingly targets the affluent top 20% because those projects offer reliable returns and can absorb high development costs.

Innovations in middle-market models

Addressing the middle-market deficit requires a fundamental shift in development and operational models. Developers are exploring several cost-saving strategies to deliver economically viable projects:

- Denser Design: Moving away from sprawling, single-story campuses toward multi-story, more urban-integrated designs that reduce land and infrastructure costs per unit.

- Technology Integration: Leveraging remote monitoring, telehealth, and automation to reduce the reliance on expensive 24/7 on-site staff for non-essential tasks, thereby lowering the operational expense ratio (OER).

- Shared Services: Implementing models that allow seniors to purchase only the services they need (a la carte) rather than being bundled into high all-inclusive monthly fees.

Investment in technology platforms that enhance operational efficiency and reduce labor intensity is critical, representing a strong investment thesis for venture capital and private equity firms targeting proptech and healthtech. However, these technological solutions require upfront capital investment that must be baked into the $300 billion needed. The challenge lies in scaling these innovative, cost-effective models rapidly enough to meet the compounding demand from the middle-income demographic.

Regulatory environment and policy risks

The regulatory landscape significantly influences the investment climate for senior housing. Because these facilities provide direct care, they are subject to rigorous state and federal health regulations, licensing requirements, and quality control standards. While necessary for patient safety, these regulations often create compliance costs and operational risks that deter capital. Changes in reimbursement rates—particularly for Medicare and Medicaid—introduce significant financial uncertainty for operators.

For example, fluctuations in the Patient Driven Payment Model (PDPM) used for skilled nursing facilities can drastically alter revenue streams and profitability within a single fiscal quarter. Investors must constantly assess regulatory risk alongside market risk. Furthermore, the lack of standardized national definitions for different senior housing levels (e.g., assisted living versus personal care) creates jurisdictional complexity that complicates large-scale, multi-state portfolio investments.

Policy levers for mitigating investment risk

Policymakers can strategically mitigate some of this risk to encourage greater private capital flow. Standardizing licensing across state lines for large operators would create economies of scale and reduce compliance overhead. More predictable, multi-year funding mandates for public reimbursement programs would allow operators and investors to model cash flows with greater certainty.

- Standardized Data: Mandating the collection and public dissemination of standardized operational and quality metrics (like infection rates and staffing ratios) could improve transparency for investors, allowing for better risk assessment.

- Zoning Reform: Streamlining local zoning and permitting processes for senior housing, which frequently face ‘Not In My Backyard’ (NIMBY) opposition, could accelerate development timelines and reduce soft costs.

- Workforce Development: Direct policy investment into training and apprenticeship programs for elder care workers could stabilize the labor pool, addressing the single largest operational risk factor cited by institutional investors.

The intersection of housing policy and healthcare policy is where the most effective solutions lie. Unless the regulatory environment evolves to support integrated models and reduce arbitrary compliance burdens, the perceived risk will continue to suppress the deployment of capital needed to close the substantial $300 billion senior housing investment gap.

Macroeconomic implications of the senior housing shortage

The failure to adequately house and care for the aging population is not just a sectoral issue; it poses systemic risks to the broader economy. A shortage of affordable and appropriate senior housing leads to several negative macroeconomic feedback loops.

First, it prolongs the time seniors occupy traditional single-family homes, reducing housing inventory for younger families and exacerbating the general housing affordability crisis. This ‘lock-in effect’ restricts labor mobility and contributes to wealth inequality. Second, inadequate senior care facilities place immense stress on family caregivers, many of whom are forced to reduce their working hours or exit the labor force entirely. This reduction in the prime working-age labor pool acts as a drag on productivity and GDP growth.

Impact on healthcare expenditure

Perhaps the most significant economic consequence is the inevitable increase in public healthcare expenditure. When seniors lack access to preventative, supportive housing, they are more likely to experience acute health episodes that require expensive hospitalizations. According to health economists, supportive senior living environments can reduce preventable hospital visits by as much as 20% to 30% compared to isolated living arrangements.

- Fiscal Burden: Unmet senior housing needs translate into higher Medicare and Medicaid costs, shifting the financial burden from private investment (the $300 billion gap) to public expenditure.

- Real Estate Market Distortion: The lack of appropriate senior housing distorts the residential real estate market, contributing to inventory scarcity and price appreciation in traditional housing segments.

- Labor Force Participation: The need for family caregiving is estimated to cost the US economy billions annually in lost wages and productivity, further justifying strategic investment in institutional senior care.

Addressing the senior housing investment gap is therefore an economic imperative, not merely a social one. Strategic capital deployment now represents a preventative measure against exponentially higher future costs associated with healthcare crises and labor market contraction. The scale of the $300 billion figure underscores the urgency required from institutional investors who seek both financial returns and positive social impact.

Opportunities for institutional investors and private equity

Despite the challenges, the structural demand created by the aging population presents compelling long-term opportunities for institutional capital capable of navigating the operational complexities. Private equity funds and specialized real estate investors are increasingly viewing senior housing as a counter-cyclical investment, offering resilient demand regardless of general economic cycles.

The investment thesis hinges on the fact that while construction starts may be volatile due to interest rates, the underlying demographic demand is fixed and growing. Investors who can successfully execute operational turnarounds or develop scalable, cost-efficient models for the middle market stand to capture significant market share and achieve superior risk-adjusted returns over a 10- to 15-year horizon.

Emerging investment strategies

Investors are moving beyond simple core-asset acquisitions into more complex, value-add and opportunistic strategies:

- Value-Add Repositioning: Acquiring older, underperforming facilities, investing capital to modernize them, and implementing professional management to stabilize occupancy and margins. This approach mitigates some of the high construction costs associated with ground-up development.

- Integrated Care Platforms: Investing in operators that successfully integrate senior housing with ancillary health services (e.g., physical therapy, primary care clinics on-site), creating higher revenue per resident and better health outcomes.

- Debt and Mezzanine Financing: Providing alternative financing solutions (preferred equity or mezzanine debt) to developers who struggle to secure conventional senior debt, often commanding higher yields to compensate for the elevated risk.

The key to successful investment in this sector is due diligence that extends beyond real estate metrics to include detailed analysis of local labor markets, regulatory compliance history, and operator quality. For investors seeking to address the $300 billion senior housing investment gap, the focus must shift from viewing these assets solely as real estate to recognizing them as essential health infrastructure requiring patient, strategic capital.

| Key Factor/Metric | Market Implication/Analysis |

|---|---|

| $300 Billion Gap Estimate | Represents required capital for new unit construction over the next decade; signals massive unmet demand and potential for high long-term returns. |

| 80+ Population Growth | Projected to double by 2040, creating inelastic demand for high-acuity assisted living and memory care units. |

| High Operational Cost (OER > 65%) | Requires specialized operational expertise and technology integration to maintain margins; deters purely real estate-focused investors. |

| Middle Market Affordability | 54% of future seniors are middle-income; requires innovative, lower-cost operating models and potential government subsidies to serve. |

Frequently asked questions about the senior housing investment gap

The $300 billion estimate derives from the capital needed to construct approximately 800,000 new units by 2035, factoring in average development costs exceeding $350,000 per unit for assisted living and memory care, according to NIC data. This addresses the demand surge from the rapidly aging 80+ population cohort.

Higher interest rates significantly increase the cost of construction debt, raising the hurdle rate for new projects. This financial pressure makes many developments, particularly those targeting the lower-margin middle market, financially unviable, thereby widening the existing investment gap.

The primary risk is labor cost volatility and availability. The high operational expense ratio (OER), driven by the need for specialized medical staff like CNAs, is severely impacted by persistent labor shortages, which directly pressures Net Operating Income (NOI) and operator margins.

No. While healthcare REITs like Welltower and Ventas are crucial capital sources, their focus often leans toward stabilized or acquired assets. Closing the $300 billion gap requires substantial greenfield development, which necessitates public-private partnerships and government support to mitigate development and regulatory risks.

Investors are exploring expanded use of FHA Section 232 loans, utilizing Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) tailored for seniors, and integrating Social Impact Bonds tied to improved health outcomes to attract mission-driven and ESG-focused institutional capital into the sector.

The bottom line

The $300 billion senior housing investment gap represents a clear, quantifiable market failure where massive demographic demand is stifled by high capital costs, operational complexity, and regulatory uncertainty. For institutional investors, this presents a unique long-term opportunity, provided they approach the sector not merely as real estate, but as essential infrastructure requiring a sophisticated understanding of healthcare economics and labor management. The market indicates that successful strategies will focus on scalable, middle-market solutions and integrated care models that can deliver stable returns while mitigating the inherent risks. Going forward, market participants must closely monitor policy shifts regarding FHA lending, state-level workforce development initiatives, and the sustained performance of specialized healthcare REITs as key indicators of progress in closing this critical financial shortfall.