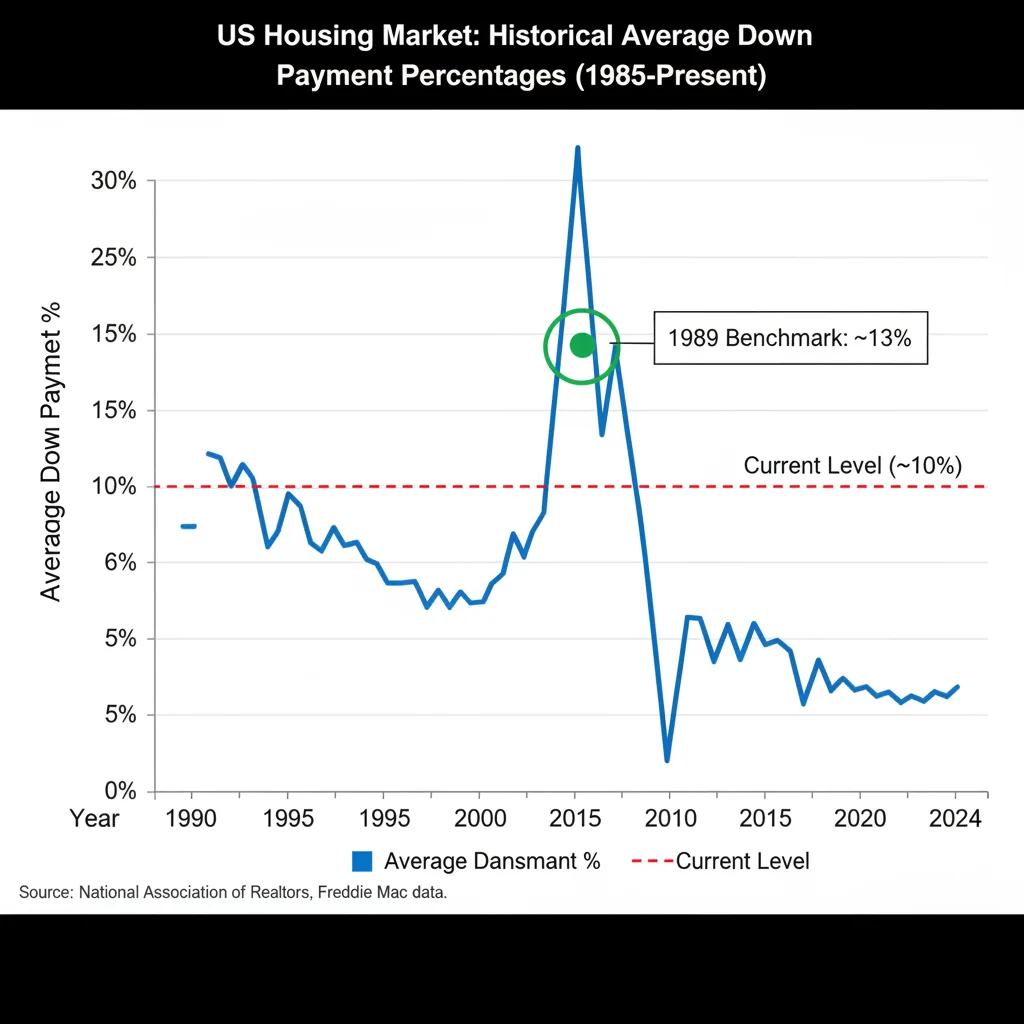

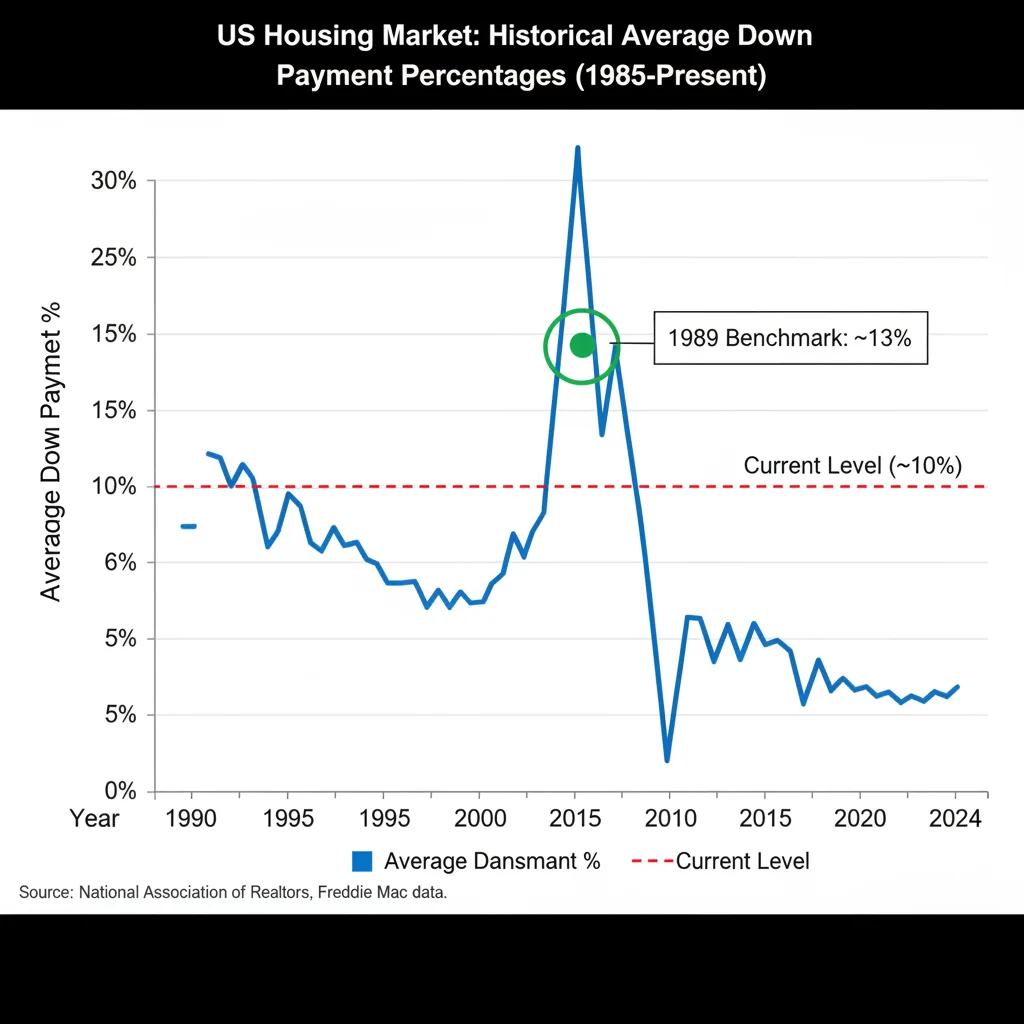

10% Down Payment: Housing Market Shift Mirrors 1989 Levels

The return of the 10% down payment as a common threshold in the U.S. housing sector, mirroring levels observed in 1989, is strategically increasing the purchasing power of borrowers while shifting the risk profile for mortgage originators and insurers.

The landscape of U.S. residential finance is undergoing a significant, data-driven transformation. For the first time in over three decades, the effective average down payment for conventional mortgages is gravitating towards the 10% mark, a financial metric last consistently recorded near these levels in 1989. This structural shift, encapsulated by the phrase Your Down Payment Just Got Bigger: 10% Down Now Matches 1989 Levels, represents a dual response by lenders and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) to persistent affordability constraints and elevated interest rates. This development directly impacts millions of aspiring homeowners, particularly first-time buyers who often struggle to accumulate the traditional 20% down payment required to avoid mandatory private mortgage insurance (PMI). Analyzing this trend requires precision, examining the underlying economic drivers, the regulatory frameworks facilitating this change, and the potential implications for systemic housing risk.

The Economic Calculus Behind the 10% Threshold

The convergence of high home prices and elevated mortgage rates has dramatically inflated the cash required to close a home transaction. As of Q3 2024, the median sale price of an existing home in the U.S. exceeded $400,000, according to the National Association of Realtors (NAR). A traditional 20% down payment on a home at this price point requires $80,000 in liquid capital, a formidable barrier for median-income households. The strategic shift toward lower down payment options is an attempt to restore market liquidity and accessibility without sacrificing core underwriting standards.

Lenders, backed by evolving guidelines from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are increasingly utilizing sophisticated risk modeling to justify lower equity requirements. This is not a return to the subprime lending practices of the mid-2000s; rather, it focuses on high-quality borrowers with strong credit profiles (FICO scores typically above 720) but insufficient savings reserves. The goal is to maximize the pool of eligible buyers who demonstrate financial discipline but lack the generational wealth often needed for a 20% down payment.

Affordability Crisis and the Savings Gap

The primary driver for the adoption of the 10% down payment standard is the widening gap between income growth and housing cost appreciation. Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis indicates that while median household income has increased, the pace of home price appreciation, particularly since 2020, has far outstripped wage growth. This disparity makes saving the requisite 20% down payment an ever-lengthening endeavor, especially for younger demographics grappling with student loan debt and inflationary pressures.

- Home Price-to-Income Ratio: This metric has reached historical highs in many major markets, requiring prospective buyers to dedicate a significantly larger portion of their income to housing costs than in previous decades.

- First-Time Buyer Median Age: The median age of a first-time homebuyer has climbed to 36, reflecting the increased time necessary to accumulate adequate savings for closing costs and down payments.

- Mortgage Payment Shock: With 30-year fixed mortgage rates hovering around 7.0% as of late 2024, lowering the down payment requirement reduces the immediate cash outlay, making the monthly payment the critical affordability constraint, rather than the initial capital barrier.

This re-emphasis on the 10% down payment is, therefore, a targeted mechanism to alleviate the initial capital hurdle, allowing more qualified borrowers to enter the market based on their capacity to manage monthly debt obligations rather than their accumulated savings.

Regulatory Frameworks and GSE Influence

The ability of the market to sustain a lower down payment average is fundamentally dependent on the backing and risk management protocols established by government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These entities purchase or guarantee the vast majority of conventional mortgages in the United States, effectively setting the standard for risk tolerance and underwriting.

The movement toward 10% as a standard benchmark is underpinned by specific GSE programs designed for low down payments, such as Fannie Mae’s 97% Loan-to-Value (LTV) offerings. While 3% down payment programs exist, the 10% figure often represents the sweet spot where the borrower has sufficient equity to mitigate early default risk, and the private mortgage insurance (PMI) premium remains manageable. This equilibrium is crucial for maintaining the stability of the secondary mortgage market.

The Role of Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI)

When a borrower puts down less than 20%, lenders require PMI to protect against potential default losses. The cost and structure of PMI have evolved significantly since 1989. Modern PMI is highly risk-adjusted, meaning a borrower with excellent credit will pay substantially less for insurance than one with a moderate FICO score, even at the same 90% LTV ratio. This precise risk pricing is a key innovation that separates today’s housing finance environment from earlier decades.

Furthermore, the ability to cancel PMI once the borrower’s equity reaches 20% of the home’s original value (or current appraised value in some cases) provides a clear financial incentive for buyers to choose the 10% or 15% path over government-backed loans like FHA, which typically carry mortgage insurance premiums for the life of the loan unless refinanced. Analysts at Moody’s Investor Service estimate that the efficiency of PMI pricing has contributed to a 15% reduction in credit losses for GSEs compared to the early 2000s, even on high LTV loans.

Historical Context: Why 1989 Matters

The year 1989 serves as a crucial benchmark because it represents a period of relative normalcy in housing finance, situated between the high-inflation era of the 1970s and the explosive deregulation and subsequent crisis of the 2000s. In 1989, the average conventional down payment hovered around 10% to 12%. This level was sustainable because home price growth was generally more aligned with wage growth, and underwriting standards, while less digitized, were fundamentally sound.

Shifting Risk Profiles Post-2008

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the average down payment surged, driven by heightened regulatory scrutiny and lender risk aversion. For much of the 2010s, the de facto standard often exceeded 15%, and for many conventional loans, 20% was the baseline expectation. This risk-off approach restricted market access but significantly lowered default rates.

The return to the 10% down payment level today is not merely cyclical; it reflects advancements in data analytics. Modern lenders can assess default risk with far greater precision than in 1989 or 2006. Factors such as debt-to-income (DTI) ratios, residual income analysis, and employment stability are weighted heavily, mitigating the perceived risk associated solely with a smaller equity stake.

- Pre-Crisis (2000-2007) LTV Risk: High LTV loans were often packaged with weak documentation and low FICO scores, leading to systemic failure.

- Current LTV Risk: High LTV loans are concentrated among prime and near-prime borrowers, typically resulting in lower expected default frequency, even under economic stress.

- Foreclosure Timelines: The extended foreclosure process in many states means that even if a borrower defaults, the 10% equity provides a crucial buffer for the lender to recover costs, a mechanism that was less effective during the rapid price declines of the Great Recession.

Implications for First-Time Buyers and Market Dynamics

The most immediate beneficiaries of the renewed focus on the 10% down payment are first-time homebuyers and younger professionals who possess high earning potential but limited savings. This group constitutes a significant source of demand that has been artificially suppressed by the high barrier to entry. Increasing their access injects essential liquidity into the housing market, particularly in entry-level segments.

Increased Competition in Starter Homes

While lower down payments increase access, they also intensify competition, especially in the starter home category (homes priced below the median). If a larger cohort of buyers suddenly qualifies, demand accelerates, potentially putting upward pressure on prices. This scenario is a critical concern for market stability, especially if housing supply remains constrained.

Economists at Goldman Sachs project that a 5% increase in the number of qualified buyers due to reduced down payment requirements could lead to a 1.5% median price increase over the subsequent 18 months, assuming all other factors remain constant. This suggests that while individual buyers benefit from reduced upfront costs, the collective effect may slightly erode affordability through price inflation.

The Trade-off: Lower Upfront Cost vs. Higher Long-Term Debt

A 10% down payment means the borrower finances 90% of the home value, resulting in a larger principal balance compared to a 20% down payment. Given the current high interest rate environment, this larger loan amount translates into significantly higher total interest paid over the life of the loan. For a $400,000 home, taking out a $360,000 loan (10% down) instead of a $320,000 loan (20% down) at a 7.0% interest rate could add tens of thousands of dollars in interest expense over 30 years.

Therefore, while the 10% down payment offers immediate relief, prospective buyers must perform a rigorous cost-benefit analysis, factoring in the added cost of PMI and the increased total interest expense. Financial planners often advise maximizing the down payment to reduce long-term exposure, but for many, the time value of money—getting into a home sooner and building equity—outweighs the incremental interest cost.

Regional Variations and Market Segmentation

The adoption and impact of the 10% down payment trend are not uniform across the United States. Markets characterized by high volatility, such as those in coastal California and parts of the Northeast, traditionally see higher average down payments, often closer to 25% for non-jumbo loans, due to elevated price points and fierce competition. Conversely, markets in the Midwest and South, where home prices are closer to the national median, are experiencing a more pronounced shift toward the 10% benchmark.

The Jumbo Loan Divide

The shift primarily affects conforming mortgages—those eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Jumbo mortgages, which exceed the GSE conforming loan limits (currently set near $766,550 in most parts of the country), maintain stricter underwriting standards. Lenders originating jumbo loans typically require a minimum of 15% to 20% down, reflecting the higher concentration of risk they retain on their balance sheets, as these loans are not guaranteed by the GSEs.

- High-Cost Areas: In cities like San Francisco or New York, where the median home price far exceeds the conforming limit, the 10% down standard remains less prevalent for the general market.

- Mid-Tier Markets: Cities like Dallas, Atlanta, and Phoenix are seeing the most significant increase in 10% down payment usage, facilitating smoother transitions for middle-income buyers.

- Credit Profile Segmentation: Even within the 10% down payment category, there is strong segmentation. Borrowers with FICO scores above 760 are receiving the most favorable terms, including lower PMI rates, underscoring the market’s continued focus on credit quality over simple equity percentage.

Risk Management and Economic Headwinds

The financial community remains acutely aware of the systemic risks associated with high Loan-to-Value (LTV) lending. The key difference between the current environment and the pre-2008 era lies in the quality of the underlying loans and the rigorous stress testing performed by regulators and lenders. The move to the 10% down payment is a calculated risk expansion, not an indiscriminate loosening of standards.

Stress Testing and Economic Buffers

Federal regulators, including the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), mandate that GSEs and large banks maintain sufficient capital buffers to withstand severe economic contractions, including scenarios involving significant home price declines (e.g., 20% or more). This capital requirement provides a structural safeguard against widespread defaults that might occur if a sudden economic shock were to materialize. Furthermore, the underwriting process now incorporates more stringent verification of income and assets, preventing the documentation fraud prevalent in the mid-2000s.

However, analysts at Fitch Ratings caution that any major economic downturn resulting in widespread job losses, coupled with a simultaneous dip in home values, could test the resilience of these lower-equity loans. The average borrower taking a 10% down payment has less immediate equity to absorb a price correction before falling underwater on their mortgage, potentially increasing voluntary default rates if employment insecurity rises.

The overall market sentiment, however, remains cautiously optimistic. The high concentration of prime borrowers in the 10% down segment suggests that these loans are structurally safer than those originated in past high-LTV cycles. The emphasis is on long-term stability: providing access to the market while maintaining the integrity of the financial system through robust underwriting criteria.

| Key Metric | Market Implication/Analysis |

|---|---|

| 10% Down Payment (90% LTV) | Significantly lowers the cash requirement for closing, increasing market access for creditworthy first-time buyers relative to the 20% standard. |

| Increased PMI Utilization | Mandatory private mortgage insurance ensures lenders are protected, but adds to the borrower’s monthly expense until 20% equity is reached. |

| High FICO Requirement (>720) | Underwriting remains stringent, focusing eligibility on borrowers with proven financial stability, mitigating the historical risk associated with high LTV loans. |

| Historical Benchmark (1989) | Suggests a return to a pre-deregulation standard, emphasizing controlled risk expansion supported by modern data analytics and credit scoring models. |

Frequently Asked Questions about the 10% Down Payment Shift

Frequently Asked Questions about the 10% Down Payment Shift

While FHA loans require only 3.5% down, they typically impose mortgage insurance premiums (MIP) for the life of the loan, regardless of equity. A 10% conventional loan allows the borrower to cancel Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI) once 20% equity is achieved, offering a significant long-term cost advantage for buyers with strong credit profiles.

Yes, generally. Lenders often price risk by offering slightly higher interest rates (0.125% to 0.250%) for loans with lower down payments (LTV above 80%) compared to a 20% down payment. However, this increase is typically minor for borrowers maintaining high FICO scores above 740, according to mortgage rate data from late 2024.

The primary risk is a reduced equity buffer against home price declines. If a borrower uses a 10% down payment and the local market experiences a 15% correction, the borrower immediately falls underwater (owes more than the home is worth), increasing the likelihood of strategic default during job loss or financial distress.

PMI can be canceled when the loan balance reaches 80% of the home’s original value, or sometimes the current appraised value, depending on the lender and loan age. With only 10% initial equity, cancellation typically requires several years of principal payments or a significant increase in home value through market appreciation or improvements.

For standard conventional 10% down loans (90% LTV), there are generally no strict income limits, provided the borrower meets the debt-to-income and credit score requirements. However, certain special assistance programs or 3% down programs offered by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac often impose specific income caps designed to target low-to-moderate income borrowers.

The Bottom Line: Navigating Accessibility and Risk

The stabilization of the average conventional down payment at or near 10%, a level last prominent during the economic structure of 1989, represents a calculated pivot in U.S. housing finance. This shift is a direct, data-driven response to the persistent dual challenge of high home prices and elevated borrowing costs, aiming to increase accessibility for well-qualified buyers without compromising the systemic stability achieved post-2008. For the individual consumer, the 10% down payment is a powerful tool against the savings barrier, but it necessitates a careful consideration of higher long-term debt and the cost of PMI. Going forward, market participants, including investors holding mortgage-backed securities, must monitor two critical variables: the sustained quality of credit profiles within the 90% LTV segment and the trajectory of home price appreciation, which determines how quickly these borrowers build protective equity buffers. Should the economy remain robust, supporting employment and wages, this return to 10% down will likely be viewed as a successful, necessary adjustment to modern housing economics; however, any significant recessionary pressure will serve as the ultimate stress test for this renewed appetite for lower-equity lending.