Personal Savings Rate at 4.6%: Are Americans Prepared for Emergencies?

With the personal savings rate hovering at 4.6%, financial analysts question whether American households have built sufficient emergency buffers to withstand unexpected financial shocks, especially given elevated consumer debt levels.

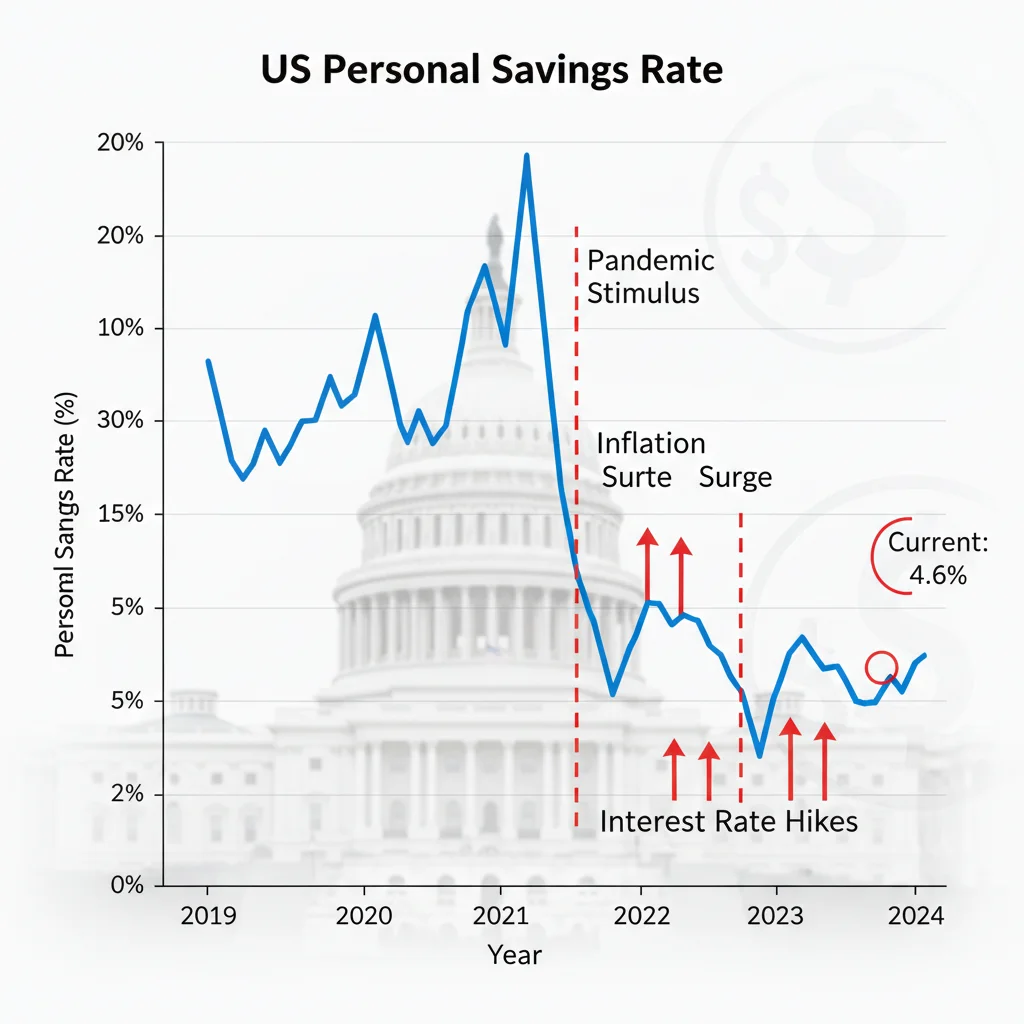

The latest Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) data indicates the US American Savings Rate, or personal savings rate, is holding around 4.6%. This figure, significantly below the pre-pandemic average of 7% to 8% and the emergency spikes seen in 2020 and 2021, raises a critical question for economic stability and household resilience: Personal savings rate at 4.6%: Are Americans saving enough for emergencies? This low rate suggests a substantial portion of US households may lack the buffer needed to absorb unforeseen expenses like medical bills, job loss, or major car repairs, challenging the narrative of a robust consumer base amid persistent inflationary pressures.

Understanding the 4.6% Personal Savings Rate: Context and Historical Comparison

The personal savings rate is defined as the percentage of disposable personal income that people save. The current reading of 4.6% is not an arbitrary number; it reflects the aggregate behavior of millions of American consumers navigating a complex economic landscape characterized by high interest rates and sticky inflation. Historically, periods of economic uncertainty often see an elevated savings rate as consumers become cautious. Conversely, a low rate often signals that households are prioritizing current consumption—or, more concerningly, are being forced to spend nearly all their income due to rising costs.

During the height of the pandemic stimulus in April 2020, the rate skyrocketed to an unprecedented 33.8%. This surge was driven by government transfers and reduced spending opportunities. However, as those funds were drawn down and consumption normalized, the rate plummeted. The current 4.6% figure is closer to recessionary lows seen in the mid-2000s than to the average sustained levels seen prior to the 2008 financial crisis. Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis note that for the US economy to maintain stability, a savings rate closer to 6% or 7% provides a healthier foundation for consumer preparedness and future investment. The sustained deviation below this historical comfort zone is a key indicator of underlying financial fragility.

The erosion of pandemic-era savings buffers

A significant factor contributing to the low rate is the depletion of the excess savings accumulated during the pandemic. Data from the San Francisco Fed suggests that nearly all of the roughly $2.1 trillion in excess savings accumulated by US households between March 2020 and August 2021 has been spent. This spending was initially fueled by pent-up demand and later necessitated by inflation, which peaked at 9.1% in June 2022. This depletion means that many households are now relying solely on current income for expenses, with little to nothing left over for savings.

- Inflationary Pressure: High costs for essentials (housing, food, energy) consume a larger portion of disposable income, reducing the capacity to save.

- Debt Burden: Elevated credit card balances and high interest rates (with the average credit card APR exceeding 21% in Q3 2024, according to the Fed) divert funds away from savings.

- Wage Growth Lag: While nominal wages have grown, real wage growth, adjusted for inflation, has been insufficient for many low- and middle-income earners to rebuild savings buffers effectively.

The implications of the 4.6% rate extend beyond individual wallets; they affect macroeconomic resilience. A financially stretched consumer base is less likely to sustain future consumption booms and more vulnerable to systemic shocks, potentially accelerating any future economic downturn. This creates a difficult balancing act for the Federal Reserve as it manages inflation while monitoring consumer health.

The Emergency Fund Metric: How Much is Enough?

The core purpose of personal savings, particularly the portion earmarked for emergencies, is to create a financial safety net. Financial planning consensus typically recommends an emergency fund equivalent to three to six months of essential living expenses. However, this benchmark varies significantly based on household stability, employment sector, and insurance coverage.

A recent survey by Bankrate indicated that only 44% of Americans could cover a $1,000 unexpected expense using savings, down from 51% in 2021. This suggests that even small financial shocks can force a substantial number of households into debt or financial distress. For the average American household, essential monthly expenses—including housing, utilities, and debt payments—often exceed $4,000, meaning a six-month buffer requires $24,000 or more. The median savings account balance is often cited significantly lower than this required threshold, highlighting the disconnect between the recommended safety net and reality.

Defining ‘Essential Living Expenses’ in the current economy

The calculation of an adequate emergency fund has become more challenging due to the persistent rise in housing and healthcare costs. These non-discretionary expenses have outpaced general inflation in many regions. For example, the national median rent increased by approximately 20% between 2020 and 2023, according to Redfin data, significantly raising the required size of a three-to-six-month emergency fund.

Furthermore, job market uncertainty, particularly in sectors sensitive to interest rates like technology and real estate, necessitates a larger buffer for many workers. Analysts at JPMorgan Chase suggest that workers in volatile industries should aim for closer to nine months of expenses, reflecting the extended time it might take to secure comparable employment after a layoff. This nuance is often lost when discussing the aggregate 4.6% savings rate.

- Risk Management Threshold: Three months of expenses is considered the bare minimum for stable, dual-income households with secure employment.

- Optimal Buffer: Six to nine months is the ideal target for single-income households, self-employed individuals, or those in cyclical industries.

- Hidden Costs: Emergency savings must also account for high-deductible health plans, which can require thousands of dollars out-of-pocket before insurance coverage begins.

The structural inadequacies in emergency preparedness revealed by the low savings rate suggest that millions of Americans are operating without a meaningful financial safety net. This lack of resilience translates into higher reliance on high-interest credit, creating a cyclical trap of debt that further impedes future saving capacity.

The Impact of Consumer Debt on Savings Capacity

The relationship between consumer debt and the personal savings rate is inverse and highly correlated. As of Q3 2024, total household debt in the US stood near $17.9 trillion, with rising delinquency rates, particularly among younger borrowers and those with subprime credit scores, according to the New York Fed. The surge in high-interest debt directly competes with savings goals.

The cost of carrying debt has been amplified by the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate hikes since 2022. Higher rates mean a larger portion of monthly income is dedicated to interest payments rather than principal reduction or savings contributions. For example, a household carrying a $5,000 credit card balance at a 22% APR spends nearly $1,100 annually just on interest, funds that could otherwise contribute significantly to a 401(k) match or an emergency fund.

The burden of non-mortgage debt

While mortgage debt constitutes the largest portion of household liabilities, non-mortgage debt—specifically credit cards and auto loans—is often the most detrimental to short-term savings capacity. Credit card balances alone have hit record highs, surpassing $1.1 trillion. This reliance on revolving credit suggests that for many households, debt is not merely financing large purchases but is being used to cover basic living expenses, a classic sign of financial strain.

Economists frequently look at the Debt Service Ratio (DSR), which measures the ratio of household debt payments to disposable personal income. While the aggregate DSR remains manageable compared to pre-2008 levels, the distribution is highly uneven. Lower-income quartiles often face DSRs that are unsustainable, forcing them to prioritize immediate debt servicing over long-term financial security, thus restricting the ability of the overall population to lift the American Savings Rate.

- Credit Card Utilization: High utilization rates signal dependency on credit, diverting funds from savings.

- Auto Loan Delinquencies: Rising serious delinquency rates (90+ days past due) for auto loans indicate acute financial distress among a growing segment of the population.

- Student Loan Payments: The resumption of federal student loan payments further strained budgets, estimated to reduce consumer spending power by billions monthly, thereby limiting savings potential.

The interplay of low savings and high debt creates a brittle financial ecosystem. If a minor recession or unexpected unemployment wave hits, the lack of emergency buffers combined with high debt obligations could trigger a significant spike in defaults and a sharp contraction in consumer spending, impacting the broader economy.

Macroeconomic Implications of a Sub-Optimal Savings Rate

From a macroeconomic perspective, the 4.6% personal savings rate presents a dichotomy. On one hand, low savings translate into high consumption relative to income, which fuels aggregate demand and contributes to GDP growth in the short term. On the other hand, sustained low savings reduce the domestic pool of capital available for investment, potentially increasing reliance on foreign capital and making the US economy more susceptible to global financial shifts.

Furthermore, the low savings rate acts as a constraint on monetary policy effectiveness. When the Federal Reserve attempts to slow the economy by raising interest rates, financially fragile consumers are hit harder and faster. This immediate impact on highly leveraged households can lead to sudden drops in demand, making the Fed’s goal of engineering a “soft landing” more difficult and increasing the risk of an abrupt economic contraction.

The role of fiscal policy and wealth inequality

The aggregate savings rate masks significant disparities across income levels. High-income earners often maintain substantial savings and investment portfolios, while lower- and middle-income groups struggle to save anything at all. This wealth inequality means that the 4.6% figure is heavily skewed by the top earners, making the true financial vulnerability of the median American household much higher than the headline number suggests.

Fiscal policies, such as tax structures and social safety nets, play a crucial role in influencing savings behavior. Targeted stimulus during the pandemic temporarily boosted savings for many, but the current policy environment offers fewer direct incentives for low- and moderate-income individuals to build liquid reserves. Analysts often point to the need for policy interventions that encourage automatic savings mechanisms and financial literacy education to address this structural deficit.

- Capital Formation: Low domestic savings necessitate higher borrowing from international markets, potentially weakening the US dollar over the long term.

- Consumer Confidence: Financial insecurity erodes consumer confidence, which can lead to rapid, defensive cuts in discretionary spending during times of economic stress.

- Systemic Risk: Widespread household financial fragility increases systemic risk for the banking sector, particularly in consumer lending and credit card markets.

In essence, while the US economy appears robust on the surface, the underlying savings metric reveals a vulnerability. A national savings rate of 4.6% suggests that a significant portion of the consumer base is ill-equipped to act as a resilient absorber of economic shocks, placing undue pressure on future government intervention and social services.

The Behavioral Economics of Savings and Emergency Funds

Beyond macroeconomic forces, personal savings behaviors are deeply influenced by psychological factors. The current low rate is not simply a function of insufficient income; it also reflects behavioral biases such as present bias, optimization fatigue, and inertia. Present bias, the tendency to prefer immediate gratification over future reward, often leads individuals to prioritize current spending over long-term savings goals, even when they know building an emergency fund is critical.

The complexity of modern financial products and the sheer number of competing financial priorities—retiring, saving for college, paying down debt—can lead to optimization fatigue, where individuals simply default to the easiest path, which is often not saving. Financial institutions and employers have recognized this and are increasingly implementing ‘nudges’ to overcome inertia, such as automatic enrollment in retirement plans and auto-transfer features for savings accounts.

The ‘Saving for a Rainy Day’ mentality shift

The traditional concept of saving for a ‘rainy day’ has evolved. Today, many Americans view their emergency fund not as a dedicated cash reserve but as available credit line—a dependence on credit cards or home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) to bridge financial gaps. While credit offers immediate liquidity, it comes at a significant interest cost, turning a temporary crisis into a long-term financial burden.

Behavioral research suggests that framing savings in terms of specific goals, rather than abstract percentages, can improve compliance. For instance, saving for a “$5,000 medical deductible” is often more motivating than saving towards a general “emergency fund.” Companies that successfully integrate these behavioral insights into their financial wellness programs report higher participation rates and larger average savings balances among employees.

- Hyperbolic Discounting: The tendency to heavily discount future rewards (like financial security) in favor of smaller, immediate rewards (like discretionary purchases).

- Mental Accounting: The psychological division of money into separate categories (e.g., spending vs. saving), which can be leveraged to prioritize emergency funds if they are treated as a non-negotiable expense.

- Default Bias: The power of making saving the automatic default, such as through payroll deductions directly into a separate high-yield savings account.

To meaningfully move the 4.6% rate higher, structural changes must be paired with behavioral tools that make saving easier, automatic, and psychologically rewarding. Otherwise, even incremental increases in income may simply be absorbed by consumption or debt repayment.

Future Outlook: How Households Can Build Resilience

The trajectory of the American Savings Rate will depend heavily on the path of inflation and the Federal Reserve’s interest rate decisions over the next 12 to 18 months. If inflation continues to moderate, providing relief on essential expenses, and if the labor market remains relatively strong, households may gain marginal capacity to replenish depleted savings. However, a significant reversal requires proactive steps at the household level.

Financial experts universally recommend prioritizing the establishment of a dedicated, liquid emergency fund separate from retirement accounts. Retirement savings, while crucial, are illiquid and often penalized upon early withdrawal, making them unsuitable for short-term emergencies. The current high-interest rate environment, while painful for borrowers, offers a silver lining for savers: high-yield savings accounts (HYSAs) and short-term Treasury bills are currently offering returns well above 4.5%, providing a real incentive to hold cash.

Strategic steps for increasing liquidity

For households struggling to achieve the three-to-six-month savings goal, a phased approach is often more realistic. The first critical step should be achieving a $1,000 to $2,000 mini-emergency fund to cover minor, high-probability events such as appliance repair or minor medical bills. This prevents immediate reliance on credit cards.

Once the mini-fund is established, the focus should shift to high-interest debt reduction. Eliminating credit card debt frees up substantial monthly cash flow that can then be redirected toward building the full emergency fund. This strategy optimizes the household balance sheet by eliminating high-cost liabilities while simultaneously building a liquid asset buffer.

- Automated Transfers: Treat savings like a bill; set up automatic transfers from checking to a HYSAs on payday.

- Windfall Allocation: Allocate unexpected income (tax refunds, bonuses) 50% to debt reduction and 50% to emergency savings.

- Budget Recalibration: Conduct a rigorous review of discretionary spending to find 5-10% of monthly income that can be consistently diverted to savings without significantly impacting quality of life.

The current 4.6% personal savings rate serves as a stark reminder that aggregate economic growth does not equate to universal financial security. Building true household resilience requires disciplined, strategic saving that acknowledges the high cost of living and the unpredictable nature of financial emergencies.

The Role of Workplace Financial Wellness Programs

Employers are increasingly recognized as key players in addressing the low savings rate dilemma. Financial stress among employees leads to reduced productivity, increased absenteeism, and higher healthcare costs for businesses. Consequently, there is a growing trend toward integrating financial wellness programs that go beyond traditional 401(k) matching.

Innovative programs are focusing on emergency savings accounts (ESAs) integrated directly into payroll systems. These systems allow employees to contribute small amounts automatically, often with a micro-match from the employer, similar to retirement plans but specifically for liquid, short-term savings. This approach leverages the power of the workplace to overcome behavioral hurdles.

Case study: Employer-matched emergency savings

Pilot programs conducted by institutions like the BlackRock Emergency Savings Initiative have shown promising results. By offering a modest employer match—for instance, $0.50 for every $1 saved up to $500 annually—participation rates in ESAs can double, and employees reach the $500 savings threshold significantly faster. The key is separating this savings vehicle psychologically and physically from the employee’s regular checking account, making it harder to spend impulsively.

Furthermore, employers can offer access to low-cost financial coaching and debt management resources. Addressing high-interest debt is often the prerequisite for effective saving. By providing these tools, companies can help employees prioritize financial goals in the most economically rational order: first, secure the emergency fund; second, eliminate high-cost debt; third, maximize retirement contributions.

- Payroll Integration: Making savings automatic through payroll deduction is the single most effective tool for increasing savings rates.

- Low-Friction Access: Ensuring employees can access emergency funds quickly and without punitive fees is essential for maintaining trust and program utility.

- Holistic Wellness: Linking emergency savings to broader financial education about budgeting and debt management maximizes long-term positive impact.

The financial resilience of the American workforce is a shared responsibility. While the 4.6% rate signals consumer strain, the expansion of employer-sponsored financial wellness programs represents a viable pathway to improve household liquidity and reduce the reliance on costly credit during unexpected events.

| Key Metric | Market Implication/Analysis |

|---|---|

| Personal Savings Rate (4.6%) | Significantly below the historical 6-7% average, indicating household financial fragility and dependency on current income. |

| Emergency Fund Coverage | Fewer than half of Americans can cover a $1,000 expense from savings, increasing reliance on high-interest credit. |

| Consumer Debt Levels | Record high credit card balances, exacerbated by high interest rates, directly compete with the capacity to build savings buffers. |

| Inflation Impact | Persistent high costs, especially for housing and healthcare, erode real disposable income, forcing consumption over saving. |

Frequently Asked Questions about American Savings Rate

The rate dropped steeply because pandemic-era excess savings, fueled by government stimuli, have been largely depleted. Consumers are now spending most of their current income due to elevated inflation and the higher cost of servicing debt, limiting their ability to contribute new funds to savings accounts.

Financial experts generally recommend saving three to six months of essential living expenses. For those with volatile income or in uncertain job markets, aiming for nine months provides a safer buffer against job loss or extended financial setbacks, according to financial planning standards.

It presents a dichotomy. High rates hurt borrowers via expensive credit card and loan payments. However, they benefit savers by allowing high-yield savings accounts (HYSAs) and short-term fixed-income products to offer returns exceeding 4.5%, providing a strong incentive to accumulate liquid cash reserves.

A balanced strategy is key: secure a small, immediate emergency fund of $1,000 to $2,000 first. Then, aggressively focus on eliminating high-interest debt (like credit cards). Once debt is cleared, the freed-up cash flow should be automatically redirected to build the full three-to-six-month emergency fund.

Employers can implement automated Emergency Savings Accounts (ESAs) integrated with payroll, often with micro-matches. This behavioral nudge makes saving automatic and overcomes inertia, helping employees build liquid buffers without having to actively manage manual transfers or complex financial decisions.

The Bottom Line: Bridging the Gap Between Economic Growth and Household Security

The persistence of the 4.6% personal savings rate underscores a fundamental fragility in the US consumer landscape. While aggregate economic indicators suggest resilience, this low savings level indicates that a substantial portion of American households remains acutely vulnerable to financial shocks. This lack of emergency preparedness creates systemic risk, potentially amplifying the severity of any future economic slowdown and constraining the efficacy of monetary policy. For investors and policymakers, the key takeaway is that consumer spending, while strong now, rests on a shallow foundation of liquid assets and high levels of revolving debt. Monitoring the trajectory of consumer credit delinquencies alongside the savings rate will be essential for forecasting the durability of the current expansion. Households must recognize that personal financial resilience is not guaranteed by macroeconomic trends; it requires disciplined, strategic saving that acknowledges the high cost of living and the unpredictable nature of financial emergencies.