Federal Deficit Hits $1.8 Trillion: Market Volatility and Long-Term Risks

The significant rise in the US federal deficit to $1.8 trillion is structurally embedding higher long-term interest rates and increasing market volatility, requiring investors to re-evaluate sovereign risk premiums and portfolio allocations.

The latest official data confirming that the US federal deficit market volatility has reached an approximate $1.8 trillion underscores a critical shift in the nation’s fiscal trajectory. This figure, substantially higher than pre-pandemic averages, is not merely an accounting anomaly but a structural factor increasingly driving market dynamics and long-term economic uncertainty. The immediate consequence is felt across the Treasury market, where elevated borrowing requirements put persistent upward pressure on yields, challenging traditional asset valuations and corporate financing models. Economists at major investment banks are now integrating this persistent fiscal drag into their medium-term projections, suggesting that the era of low-cost borrowing for both the government and the private sector may be definitively over.

The structural acceleration of fiscal imbalance

The $1.8 trillion deficit mark, recorded for the most recent fiscal year, reflects a confluence of lower-than-anticipated tax receipts and persistently high mandatory spending, compounded by soaring interest payments on existing debt. This is distinct from deficits driven solely by cyclical economic downturns; this deficit is fundamentally structural, indicating that even during periods of moderate economic growth, the government’s expenditures significantly outpace revenues. Data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) indicates that interest payments alone are projected to eclipse defense spending within the next decade, transforming the profile of federal outlays.

This structural imbalance has profound implications for the national debt, which now exceeds $34 trillion. The acceleration of the deficit is primarily attributable to entitlements, healthcare costs, and, critically, the rising cost of debt servicing. As the Federal Reserve maintained higher benchmark rates (the federal funds rate resting between 5.25% and 5.50% as of Q4), the Treasury Department is forced to issue new debt at significantly higher yields than those seen in the 2010s. This creates a self-reinforcing loop: higher debt necessitates more borrowing, which in turn drives up interest costs, further expanding the deficit.

Debt servicing costs and crowding out effects

The cost of servicing the national debt has become a dominant narrative in fixed-income markets. In the last reported quarter, net interest outlays surpassed $250 billion, a year-over-year increase of nearly 35%. This dramatic rise suggests a potential ‘crowding out’ effect, where government borrowing absorbs a disproportionate share of available capital, potentially limiting credit access and raising financing costs for private sector investment. This mechanism challenges the assumption that fiscal stimulus can operate without significant real-world costs, even in a large economy like the United States.

- Increased Treasury Issuance: Higher deficits require the Treasury to increase the frequency and size of bond auctions, particularly in the 10-year and 30-year segments, testing market absorption capacity.

- Reduced Fiscal Flexibility: A growing share of the federal budget dedicated to interest payments reduces the government’s capacity to respond to future crises (e.g., recessions, geopolitical events) through discretionary fiscal policy.

- Investor Demand Shift: Institutional investors, particularly foreign central banks, are scrutinizing US fiscal stability, potentially leading to a diversification away from US Treasuries if long-term fiscal discipline is not demonstrated.

The persistence of the $1.8 trillion deficit fundamentally alters the risk calculus for investors. While US Treasuries remain the global benchmark for safety, the sheer volume of issuance and the underlying lack of fiscal control introduce a non-zero, albeit low, sovereign risk premium that was absent during periods of lower debt-to-GDP ratios. This premium manifests as elevated long-term yields, which are crucial for assessing the present value of future corporate earnings and, consequently, equity valuations.

Impact on long-term interest rates and the yield curve

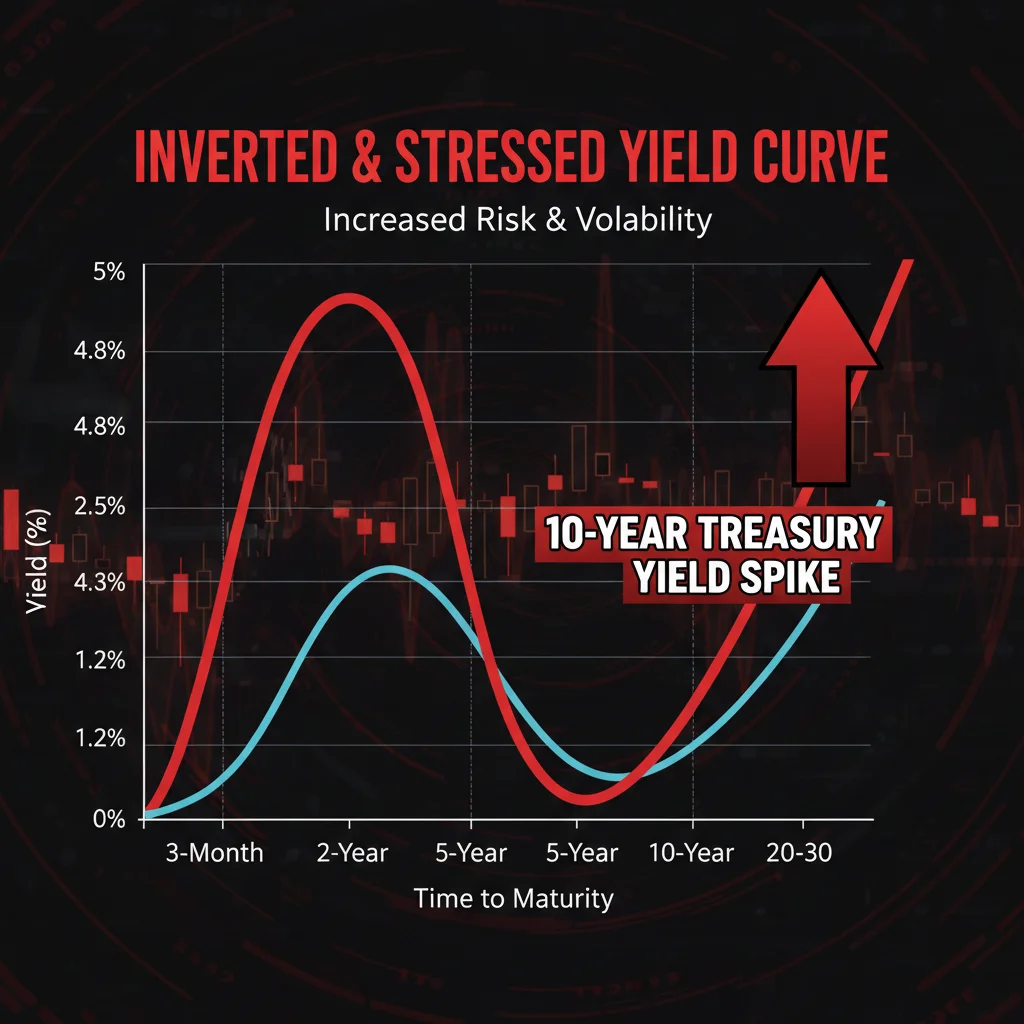

The correlation between sustained high deficits and long-term interest rates is increasingly evident. When the Treasury needs to finance a $1.8 trillion gap, the supply of debt floods the market, pushing prices down and yields up. This phenomenon has been particularly pronounced in the long end of the yield curve, specifically the 10-year and 30-year Treasury bonds, which are highly sensitive to long-term inflation expectations and fiscal solvency concerns.

Market participants are observing a steepening—or in some critical periods, a renewed inversion—of the yield curve, driven not just by the Federal Reserve’s short-term rate policy, but by the structural demands of fiscal policy. Analysts at Goldman Sachs noted in their Q4 2024 outlook that “fiscal dominance, defined as the pressure exerted by government borrowing needs on interest rates, is the single largest factor preventing a sustained decline in long-term yields below 4.5%.” This suggests that the market is pricing in a permanent increase in the cost of capital due to fiscal behavior.

The erosion of the inflation anchor

A secondary, yet critical, implication of the persistent deficit is its effect on inflation expectations. Large-scale government spending, even if financed by debt, can stimulate aggregate demand, potentially complicating the Federal Reserve’s efforts to return inflation to its target 2% rate. If the market believes that the government will eventually pressure the Fed to monetize the debt—or simply tolerate higher inflation to reduce the real value of the debt—long-term inflation expectations will drift higher. This expectation is immediately reflected in the pricing of inflation-protected securities (TIPS).

- Breakeven Inflation Rates: The 10-year breakeven inflation rate, the difference between nominal and real Treasury yields, has remained stubbornly above 2.3%, indicating that bond markets are skeptical of a swift return to pre-pandemic price stability, partly due to expansionary fiscal policy.

- Monetary vs. Fiscal Conflict: The current environment pits the Fed’s tight monetary policy against expansive fiscal policy. The deficit acts as a continuous stimulus that counteracts the Fed’s rate hikes, requiring the central bank to maintain higher rates for longer to achieve its inflation mandate.

- Term Premium Spike: The federal deficit market volatility has contributed significantly to the rise in the term premium—the extra compensation investors demand for holding long-term bonds compared to rolling over short-term bills. This premium reflects both inflation risk and fiscal risk.

For corporations, the rise in long-term rates translates directly into higher borrowing costs for capital expenditure and refinancing existing debt. Companies with substantial debt loads or ambitious growth plans relying on cheap capital face margin compression, leading to dampened investment and hiring prospects across sectors sensitive to interest rates, such as real estate and utilities. The $1.8 trillion deficit is thus a direct input into the corporate cost of capital.

Amplification of market volatility and risk premiums

The sheer size and unpredictability of the federal deficit contribute directly to increased market volatility. Uncertainty surrounding future fiscal policy—specifically, whether Congress will address the structural deficit or continue on the current path—creates significant swings in investor sentiment. This volatility is not confined to the fixed-income market; it spills over into equities and currency markets.

When the deficit figures are released or when budget negotiations stall, the equity market often reacts with sector-specific volatility. Companies reliant on government contracts or those sensitive to macroeconomic stability (e.g., financials and infrastructure) experience heightened price fluctuations. This is the essence of how the federal deficit market volatility nexus operates: fiscal instability translates into economic uncertainty, which markets abhor. The CBO’s long-term debt projections, which show the debt-to-GDP ratio climbing toward 120% by 2035, serve as a constant reminder of the underlying structural risk.

Sectoral implications of rising sovereign risk

Rising sovereign risk premiums, fueled by the persistent deficit, disproportionately affect certain sectors. Financial institutions, particularly those holding large portfolios of US Treasuries, must account for the increasing duration risk. Furthermore, sectors dependent on consumer credit and low-rate environments, such as housing and automotive, face headwinds as higher rates dampen demand and increase default risk. Conversely, sectors with strong pricing power and low capital intensity, like certain technology segments, may prove more resilient.

The US dollar itself experiences volatility. While a high deficit might typically lead to dollar depreciation due to oversupply of sovereign assets, the current global environment—characterized by geopolitical instability and high demand for safe assets—has complicated this dynamic. However, persistent fiscal deterioration erodes long-term confidence in the dollar’s status, posing a risk to its reserve currency dominance, a factor that could introduce massive volatility into global trade and finance if realized. Analysts at BlackRock suggest that while the dollar’s dominance is not immediately threatened, the fiscal path “is a long-term drag on global confidence in US assets.”

The implication for portfolio managers is clear: standard risk models must be recalibrated to account for higher structural interest rates and increased correlation between fiscal news and market movements. Diversification strategies must look beyond traditional asset classes to include inflation hedges and real assets, given the potential for the deficit to fuel inflation over the long run.

The role of quantitative tightening and debt monetization fears

The $1.8 trillion deficit is occurring concurrently with the Federal Reserve’s program of quantitative tightening (QT), where the Fed reduces its balance sheet holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. The confluence of massive Treasury issuance (to finance the deficit) and the Fed’s reduced demand (through QT) creates a supply-demand imbalance in the bond market, which fundamentally exacerbates upward pressure on yields.

The market fear, often termed ‘fiscal dominance,’ revolves around the possibility that the structural deficit will eventually become so large that the Fed is compelled to halt or reverse QT to prevent a complete breakdown in Treasury market functioning. If the Fed were forced to purchase debt to keep interest rates artificially low—a process known as debt monetization—it would signal a loss of central bank independence and likely trigger a sharp inflationary spike. While the Fed has maintained its commitment to independence, the scale of the deficit makes this scenario a persistent tail risk that contributes to federal deficit market volatility.

Comparison with historical debt crises

While the US is not currently facing a debt crisis comparable to emerging markets, historical precedents demonstrate that rapid increases in debt-to-GDP ratios can lead to sustained periods of economic stagnation and high inflation. The post-World War II debt level was high but rapidly reduced by high GDP growth and financial repression (keeping rates low while inflation ran hot). Today, US growth potential is lower, and global capital markets are hyper-aware of inflation risk, making the current fiscal situation more challenging than historical periods.

- Term Structure Volatility: The difference between the 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields has frequently whipsawed, indicating market confusion over whether the primary driver of rates is the Fed’s short-term policy or the long-term fiscal trajectory.

- Foreign Holdings Decline: Major foreign holders, such as China and Japan, have reduced their net holdings of US Treasuries, requiring domestic and institutional buyers to absorb a larger share of the new $1.8 trillion in deficit-related issuance.

- Credit Rating Scrutiny: The recent downgrade by Fitch Ratings, citing expected fiscal deterioration and high general government debt, highlights that rating agencies are actively factoring the deficit into their assessments, increasing the perceived risk of US sovereign debt.

The market’s expectation is that without substantive fiscal reform—either significant tax increases or deep spending cuts—the fiscal trajectory is unsustainable. The lack of political consensus on how to address the structural deficit means that uncertainty and volatility will remain embedded features of the US financial landscape for the foreseeable future. This requires investors to maintain a cautious stance on long-duration assets and prioritize cash flow resilience in their equity holdings.

Investment strategies in an era of fiscal dominance

Given the persistent $1.8 trillion deficit and the resulting market pressures, investors must adapt their strategies to an environment characterized by higher real interest rates and increased volatility. Traditional 60/40 portfolios face challenges, as the negative correlation between stocks and bonds, a hallmark of previous decades, has weakened due to inflation and fiscal risk simultaneously pressuring both asset classes.

The focus should shift toward companies that possess strong balance sheets, high free cash flow generation, and low reliance on external capital markets. Sector selection becomes paramount. Energy, materials, and infrastructure, which often benefit from inflation and government spending, may outperform rate-sensitive sectors like technology and consumer discretionary, although the latter may see resilience in market leaders with monopolistic characteristics.

Hedging against deficits and inflation

Effective hedging strategies in this environment involve instruments that protect capital against both unexpected inflation and sustained high interest rates. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) offer direct protection against inflation, although their real yields are now higher, making entry points crucial. Furthermore, floating-rate instruments and short-duration debt can mitigate the risk of capital loss when long-term rates rise due to persistent deficit financing.

In the equity space, companies that can pass on increased costs to consumers (pricing power) are essential. This includes certain consumer staples and healthcare providers. Conversely, companies with aggressive growth targets financed by high debt are particularly vulnerable to the structural increase in the cost of capital driven by the $1.8 trillion deficit and subsequent market volatility. Analysts at Morgan Stanley recommend an overweight stance on quality value stocks that exhibit robust earnings stability, arguing they are better insulated from macroeconomic shocks stemming from fiscal policy.

Ultimately, navigating this environment requires a dynamic approach. The market will continue to react sharply to deficit updates, CBO projections, and any legislative movement on spending or taxation. Investors must treat fiscal policy as a primary market mover, alongside monetary policy, rather than a secondary consideration. The long-term implication is a higher risk premium for all US assets until fiscal sustainability is credibly restored.

Policy paths and future deficit forecasts

The future trajectory of the federal deficit market volatility relationship hinges heavily on policy choices in Washington. Current projections suggest that without significant legislative changes, the deficit will remain structurally high, potentially exceeding $2 trillion annually in the latter half of the decade, driven by mandatory spending growth and rising interest costs. The CBO’s baseline forecast, which assumes no major policy shifts, paints a grim picture of escalating debt burdens.

Two primary policy paths are currently debated: a return to fiscal austerity, involving deep spending cuts or tax hikes, or a continuation of the status quo, potentially leading to higher inflation or slower long-term growth. The market currently prices in the latter, which is why long-term yields remain elevated. Any credible bipartisan effort to establish a long-term fiscal commission or implement structural reforms would likely be met with a sharp, positive market reaction, potentially reducing the term premium and dampening volatility.

The political economy of debt reduction

Achieving meaningful debt reduction is politically challenging, requiring trade-offs on politically sensitive programs like Social Security and Medicare, which constitute the largest components of mandatory spending. Furthermore, tax increases substantial enough to close a $1.8 trillion gap would likely face strong political opposition and could potentially slow economic growth, creating a policy paradox. The consensus among serious economic observers is that a combination of modest spending restraint, targeted revenue increases, and sustained, productivity-driven economic growth is necessary, although the timing and implementation remains highly uncertain.

The uncertainty surrounding policy action is, in itself, a source of market volatility. Every debt ceiling debate, every budget negotiation, and every CBO report introduces a period of heightened risk perception. For global financial institutions, this translates into elevated hedging costs and constrained risk-taking. The core message emanating from the $1.8 trillion deficit is that fiscal risk has transitioned from a theoretical concept to a tangible, day-to-day factor in financial market pricing.

| Key Fiscal Metric | Market Implication/Analysis |

|---|---|

| Federal Deficit Level | $1.8 Trillion deficit is structural, increasing reliance on bond issuance and driving up long-term supply. |

| Debt Servicing Costs | Interest payments projected to exceed defense spending, leading to reduced fiscal flexibility and potential crowding out. |

| 10-Year Treasury Yield | Sustained upward pressure due to high supply and fiscal risk premium, impacting corporate borrowing costs globally. |

| Market Volatility Index | Heightened volatility around fiscal deadlines and CBO reports, requiring active hedging strategies. |

Frequently Asked Questions about Federal Deficit and Market Volatility

The large deficit necessitates massive Treasury issuance, predominantly affecting the long end of the curve (10-year and 30-year bonds). Increased supply, coupled with reduced Federal Reserve demand through quantitative tightening, drives long-term yields higher, increasing the term premium and sometimes causing curve inversions.

Crowding out occurs when substantial government borrowing absorbs a large portion of available capital in financial markets. This competition for funds drives interest rates up for all borrowers, making it more expensive for private businesses and consumers to obtain credit for investment and consumption.

Yes, analysts recommend favoring companies with strong cash flow, low debt, and proven pricing power to withstand higher interest rates and potential inflation. Rate-sensitive sectors and highly leveraged companies face greater risk from the structural increase in the cost of capital.

Large deficits often signal persistent fiscal stimulus, which can counteract monetary tightening efforts. Markets may price in higher long-term inflation if they believe the government may eventually tolerate higher inflation to reduce the real burden of the massive $34 trillion national debt.

While the dollar remains dominant, sustained fiscal deterioration and high debt levels erode long-term international confidence. This increases the theoretical risk of a shift away from US assets, which could introduce substantial currency volatility and impact global trade financing over the coming decades.

The bottom line: Fiscal policy as the new market driver

The $1.8 trillion federal deficit is not merely a political talking point; it is a profound structural economic reality that has fundamentally recalibrated risk and return across global financial markets. The long-term implications are clear: the US economy must adapt to a persistently higher cost of capital, driven by the Treasury’s insatiable need to finance its fiscal gap. This reality challenges the stability of the 10-year Treasury yield—the foundation of global finance—and embeds a higher degree of federal deficit market volatility into the system.

Looking ahead, market participants must monitor two key indicators: the frequency and size of Treasury auctions, and any credible legislative movement toward long-term fiscal consolidation. Until structural reforms address the mandatory spending components and revenue shortfalls, investors should anticipate that fiscal news will carry the same, if not greater, weight than traditional monetary policy announcements. Prudence dictates maintaining robust liquidity, focusing on quality assets, and actively hedging against the tandem risks of sustained high rates and fiscal-induced inflation. The era of cheap money is over, largely due to the sheer scale of government borrowing now required to sustain current policy paths.